The Big Picture

Last week, we looked at a lot of the mechanics of writing which you can address during revision. This week, we’re going to look at the bigger picture – your story as a whole.

Last week, we looked at a lot of the mechanics of writing which you can address during revision. This week, we’re going to look at the bigger picture – your story as a whole.

Whatever your story, it will create a set of laws that govern that story’s universe. If we’re writing contemporary drama, that’s not so important, because we’re subject to the laws of everyday life – unless we incorporate something supernatural (e.g. vampires) or magical (e.g. wizards). Then we need to work out how those beings function in our society, and what laws govern them. If we’ve written sci fi, we may need to consider the physics of the universe, e.g. how fast does a ship travel, how much damage can it take in battle? If we’ve written fantasy, our universe may be populated by magic and amazing creatures, such as dragons and serpents. If a character is capable of magic, we need to determine how their magic works and when and how it can be used.

You need to know the answers to these questions when you’re writing. These laws will govern the behaviours of your characters. It’ll also create an airtight universe which won’t insult or lose the reader with inconsistencies – and readers will pick these things up. These questions themselves may never be exhibited in the story itself, but they are the framework that shapes your world, dictates causality and defines your characters’ boundaries.

There are also other obvious questions that you can ask once you’ve finished your piece, such as:

-

Is the plot sound?

As in does it make sense and there are no holes in it that would be exposed by an astute reader?

Are the characters three-dimensional?

We all have our strengths, weaknesses, desires, peeves, et al. Our characters also need to have them – particularly if you’re writing villains. Villains shouldn’t be evil for the sake of being evil. Characters should also have arcs, an evolution that occurs over the course of the story.

Is the logic of your story motivated and are the motivations of your story logical?

Characters need believable motivation for why they take the action they do. None of us do things without reasons. If your character burns down the neighbour’s house, is it believable that they would take this action? And is it believable what pushed them to this action? A neighbour might play loud music all night, every night for a month. Would that trigger you into burning their house down? Maybe not. What if your character had an ill child and the child died because they just couldn’t get the rest to recuperate? Well, that might push your character over the edge.

Are subplots and supporting characters attended?

Writing can be difficult when we’re juggling and trying to keep so many things and so many people in the air at once. It can be very easy to drop a few, forget about them, and pick them up only when they’ve been all but forgotten.

Something useful when writing a longer work, such as a book, is to diagram the book in a graph so you can get an overview of the structure.

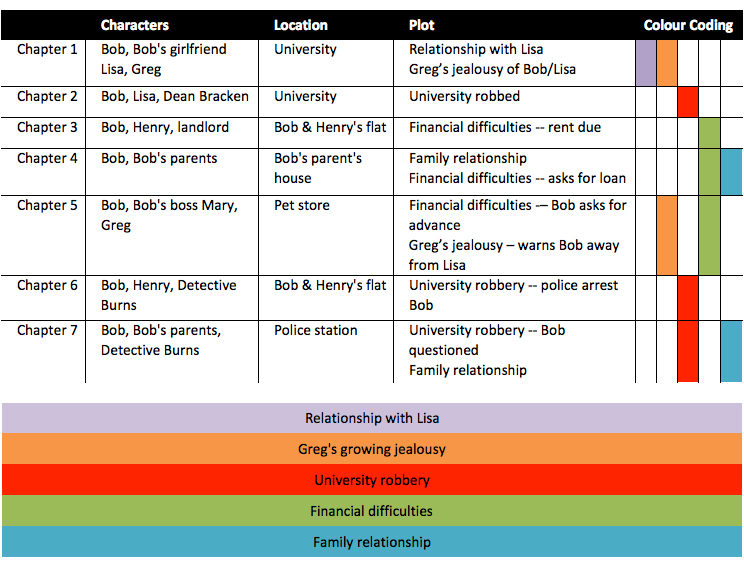

Before we proceed with that, let’s create a hypothetical novel we can work on: Bob is a 20-year-old student at university. He has a girlfriend named Lisa, although her ex Greg is not happy about their relationship and keeps trying to win Lisa back. Bob lives in a flat with his best friend Henry. They struggle to pay the rent, although Bob works after school and weekends in a pet store. When the university is robbed, Bob is incriminated and charged. He then has to clear his name.

Okay, it’s a very simple idea, but exists solely for the exercise of our diagram. In our diagram, we’d have several columns, which would list which chapter it is, the characters who appear in that chapter, the location (or locations) used in that chapter, as well as which plots and subplots have been attended. If we wanted to be really fancy (and we will, for the sake of this exercise) we could attribute a colour to each plot, and list that, too.

What we’re left with might look like this:

At a glance, we can now see how our book is unfolding, what characters and plots are being attended, and what’s being neglected.

Just from a glance, Bob’s financial difficulties dominates the story, which may be considered repetitive. Do we really need all that happening at once? Lisa appears at the beginning, and then is unsighted. Perhaps we can include her elsewhere – how about in Chapter 6, when the police come to arrest Bob? Maybe Bob and Lisa are having a romantic dinner. That would further their relationship, but also add drama since Lisa will be witness to Bob’s arrest. Henry, whilst in the book so far, doesn’t seem to feature in any storyline. Is he actually required?

This is a basic example but it does give us an overview to demonstrate how useful story diagramming can be as a tool when we revise.

LZ.

Great article. I’d just like to add that the writing program, Scrivener, can be used to help with visualising multiple plots. The writer can define their own colours for each plot or viewpoint and see the overall effect in the ‘corkboard’ view.

Thanks for spelling out such a clear concise method of revision, it’s something we all need to learn but without a plan to follow I often find myself circling the same issues over and over without resolution. Hopefully no more!