Month: June 2017

Welcome to the Busybird blog, where you can find helpful articles, updates, industry news and more. Make sure you stay up to date by signing up to our newsletter below.

Issues in Writing: Part I

June 29, 2017 The appreciation of any art form is subjective. We all have different tastes. And that’s fine. If we all had the same tastes, the world would be boring, and art would become predictable as a medium. So diversity of opinion is a good thing.

The appreciation of any art form is subjective. We all have different tastes. And that’s fine. If we all had the same tastes, the world would be boring, and art would become predictable as a medium. So diversity of opinion is a good thing.

But, when it comes to writing, there’s some things that aren’t subjective – issues of expression and grammar that are just wrong. These contribute to poor expression, lack of clarity, and weak phrasing. Addressing these as an author can help you tell the story you want to tell powerfully and engagingly.

So, over the coming weeks, we’re going to list a number of things that we see in writing when we assess and/or edit. We’ll do this in layman’s terms (for our benefit, as much as anyone’s), using before and after examples to demonstrate.

Here goes …

General Expression

Writers have a proclivity to introduce a subject in one sentence, and then expand on it in the next.

- He charged through the door. The door was gold.

He charged through the door, which was gold.

Neither of these are wrong, and you might systematically build details this way for effect. But, sometimes, it’s just because you’re feeling your way through your narrative, and this can result in details coming begrudgingly. Thus, you articulate them begrudgingly. This example could be simplified to:

- He charged through the gold door.

Passive vs Active

In a passive sentence, the action happens to the subject. In an active sentence, the subject performs the action. Active writing is concise and direct. Here are two examples of passive writing:

- The swimmer was eaten by the crocodile.

Your manuscript has been destroyed.

And written actively:

- The crocodile ate the swimmer.

I have destroyed your manuscript.

You may use passive writing for effect. Every awards show does this: ‘And the winner is …’ They do it this way to delay the announcement as long as possible, which builds the drama.

You can often identify a passive sentence by the use of ‘by’.

Is your verb strong enough?

It’s strange that in primary school and high school, we’re taught to use adverbs, but in writing, adverbs are a sign that your verb isn’t strong enough.

- She spun quickly away from him.

I ran fast down the street towards my house, scooped up the bat, and hit the burglar hard over the head.

In the first example, the verb is ‘spun’, and the adverb is ‘quickly’. But is there a stronger verb that performs the action of spinning quickly? Think about it.

In the second example, we have a number of verbs and adverbs: ran (verb) fast (adverb); scooped (verb); hit (verb) hard (adverb).

If you look at the breakdown, ‘scooped’ is a great verb. It’s creates a visual of exactly what’s happening. But what about the others? What better verbs would perform the actions we’re describing?

Correcting both examples, we might have:

- She twirled away from him.

I bolted down the street towards my house, scooped up the bat, and whacked the burglar over the head.

Obviously, there are other options. But this gives you an idea of finding strong verbs to do the job of a verb/adverb combination.

Meh Verbs

Here, we’re using verbs that don’t correlate with an action to describe what’s happening.

- I take a seat.

He shouted at me, which caused me to be upset.

My heart was beating fast.

Take (meh), caused (meh), was (meh)! Is there any power in what’s being said? Reinserting proper verbs restores conciseness of expression:

- I sit on the chair.

He shouted at me, which upset me.

My heart beat fast.

Sometimes, you might want the informality of a I take a seat. You might be trying to communicate that casualness. If you’re not, find the right verb for the right job.

Begin / Start

You begin a book. You start a car. Otherwise, ‘begin’ and ‘start’ imply actions that either are never completed, or ongoing:

- I begin to tie my shoelace.

I start to wash the dishes.

In neither example has the action been completed. It’s something that was begun … and then what happened?

- I begin to tie my shoelace, but feel a twinge in my back.

This shows us that the act was interrupted. Using ‘begin’ is logical.

But what else could happen?

- I start to wash the dishes. Bob babbles about his break-up from Mary. ‘She never listened to me,’ he says. ‘Doesn’t matter what I said.’ I put the final plate in the dish rack and turn off the taps. ‘Sorry?’ I say. ‘What were you saying?

Here, the action is ongoing as something else is happening concurrently.

These are the only times you should use ‘begin’ or ‘start’. Otherwise, be direct. Complete the action.

- I tie my shoelace.

I drink.

Seem/Seemed

Something is or it isn’t. There’s usually no ‘seemed’ about it.

- School seemed to drag even more than usual that day and I kept staring at the clock waiting for the final bell to ring.

Did school drag or didn’t it? If it did, then it didn’t seem to.

- School dragged even more than usual that day and I kept staring at the clock waiting for the final bell to ring.

You may use ‘seem’ (or any of the derivatives) if you want to communicate uncertainty, but otherwise think about how absolute whatever you’re saying is.

Nothing modifiers

If you’re going to use a modifier, be definitive. Don’t use anything that has no real qualitative measure.

- It’s virtually hopeless.

It is quite hot.

I finally got around to speaking to Jen; she was somewhat peeved it had taken me so long, but it wasn’t my fault. Basically, what had happened was the keyboard on my phone started playing up. The whole phone became practically useless.

How much is ‘virtually’? How hot is it when it’s ‘quite hot’? Words such as ‘somewhat’, ‘basically’, ‘essentially’, etc., give no definitive measure. You might use them in dialogue to convey a conversational tone (e.g in this example practically useless may be accurate), but in prose eliminate them.

Filters

Filters are words we use to connect our characters to their environment or to their inner monologue for the interpretation of the reader.

- He saw that she was wearing the blue dress he liked.

I noticed it was beginning to rain.

I realised that she didn’t love me.

We don’t need filters in writing because all the information being delivered is being delivered through the POV of our characters, whether the prose is first, second, or third person.

- She was wearing the blue dress he liked.

It was beginning to rain.

She didn’t love me.

You might use filters when you want to draw attention to a character noticing something (e.g. I noticed a drop of blood on her ear), but you can otherwise ditch them.

Expletive Construction

Expletive constructions are combinations such as ‘There was’, ‘There were’, ‘He/she was’, ‘It was’, etc.

- There were three boys sitting at the bus stop.

There was a bird singing in the tree.

It is inevitable you’ll understand.

These can be chopped and sentences rejigged to be more direct.

- Three boys sat at the bus stop.

A bird sang in the tree.

Inevitably, you’ll understand.

Clichés

Clichés are forms of expression that have become overused and lost all meaning.

- The scream echoed through the house and made my blood run cold.

What does it mean when blood runs cold? Obviously, we know what it’s intending to convey, but how effective is it? Think of an evocative way to describe the terror. Look for expressive that is unique.

In our next blog, we’ll continue looking at issues in writing.

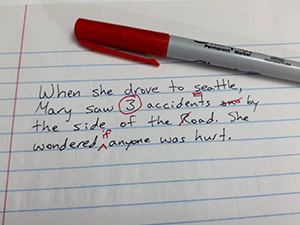

Some Editing Tips

June 15, 2017 At some point, you’re going to have to revise your writing. If you think you don’t, that you’ve produced something flawless, well, you have work to do on your attitude before you even get to your writing.

At some point, you’re going to have to revise your writing. If you think you don’t, that you’ve produced something flawless, well, you have work to do on your attitude before you even get to your writing.

You will need to revise. It’s inevitable.

A big concern is you know your work too well. You become so immersed in it, you lose objectivity. If you were aware of the issues you were introducing, you wouldn’t have introduced them to begin with. So where do you go? What do you do? How do you see your writing with new eyes?

Fortunately, there’s a few tricks that’ll help with revision.

When you finish a draft, reread, revise, reread, revise, reread, revise, ad nauseam …

The first draft should be a spill. Everything should come out. Problem here is that while you might get everything in your head out, it’s bound to be splotchy – that means there’ll be holes in the plot, in the characterisation, in the pacing … well, all of it.

This is why it’s important to revise immediately. Flesh it out while it’s fresh in your head and your imagination’s firing, offering solutions to plug those holes. And keep doing it. Do it until you feel you’re not getting anything more out of it – here, it’s important to be mindful of whether your changes are meaningful (and thus significantly improving the story) or meaningless (it doesn’t matter one way or another if the changes are implemented or not).

Put your writing away

If you’re working to a deadline, this can be hard. If you can, put your writing away for a minimum of a week. If no deadlines are looming, put it away for as long as possible, e.g. six months. You want to go back to it with a fresh perspective.

Repeat the ‘reread, revise, etc.’ step. However …

… assign each edit a different role. Your first pass might address structural issues. Your next edit might be dedicated to line-editing, e.g. poorly-phrased expression, repetition, overwriting. Something I find helpful with the latter is to read a chapter twice – the first time to familiarise yourself with it and see where things are going, the second time because you’ll now know where things are heading, where they’ve been repeated, where they go on, etc.

As an aside …

If you have more than one computer – e.g. a desktop and a laptop – and you do all your writing on one (e.g. the laptop), trying revising your work on the other. It’ll force your mind to process the information differently.

And on that …

If your writing isn’t reliant on font choices – e.g. you might have the narrative in one font, letters from a character in another, quotes from somebody else in another – change the font. Change the font colour also. Again, this forces your mind to process what it’s reading differently to how it’s done it before. If you do multiple revisions (as you should), change the font and/or the font colour each time so you’re always seeing it differently each time.

Get somebody else to read your writing

This doesn’t mean a partner, a family member, or a friend with some qualification that you correlate to writing, e.g. a Year 10 English teacher. It’s likely these people will either tell you that your work is good, or you’re wasting a time – neither are constructive comments that can help you address issues in your writing.

If you have writing friends, try them. If you can, join a workshop group. If you can afford it, get your manuscript professionally assessed by somebody trained to identify and articulate any issues, and possibly suggest solutions. The key here is finding somebody who’s going to be valuable to you.

This doesn’t mean all these people are infallible. You still need to find somebody you’ll click with. If you’re writing fantasy, and you have a (writer) friend and all they read and write is romance, they’re unlikely to gel with your work. They might. Some writers operate fine outside their own genre, but others are constricted by it. So find somebody right for you – somebody who’ll be detailed, objective, and constructive. Additionally, you wouldn’t believe the errors those seemingly qualified friends can introduce (I’ve seen this repeatedly).

Apply changes where you see fit

You don’t have to implement every bit of feedback. Remember, reading is subjective. You could bring up a plot point with ten people and get ten different opinions. You have to weigh up what’s right and going to help your writing get to its destination. Having said that, don’t be precious either. If two or more people say the same thing, there’s likely to be an issue, no matter how much you disagree. Don’t be precious. Try to genuinely appreciate what somebody is saying. If you’re not going to address their concern, have a valid reason other than, ‘You don’t get it’, or, ‘I think others would understand what I’m doing.’ Yes, there is a (remote) chance either of those rejoinders might be valid, but be as thorough as you can in that examination.

Go through the other points again

Yes. Again and again and again and again and again and again and again. Obviously, you can do this ad nauseam, until you are performing meaningless revision, e.g. swapping one adjective for another. But the more you practise editing and revision, the more you’ll grow to understand and recognise when you can consider your manuscript complete enough to send out into the world.

In summing up …

… writing isn’t meant to be easy. It’s not a pursuit where you can spew gold. Or where one reread addresses every issue your work contains.

It doesn’t happen.

The best writers aren’t the confident ones, but the insecure ones. The confident writers believe they’re infallible, their minds closed to the possibility that their writing could be improved. If there are queries, these writers don’t consider for a moment that they might be legitimate and worth exploring, but that the reader just doesn’t get it. The truth is simple: if a reader brings up a query, they’re likely going to be reflective of a readership.

The insecure writers know and understand everything that could be wrong with their writing, and strive to address and correct it over and over and over, until they get their writing the best it can be (and, even then, they may still be doubtful).

Which writer are you?

An Exploration of a Hypothetical Structure

June 1, 2017 Last blog, we structurally mapped a hypothetical story to see how it worked out. Let’s now look at the questions that came up.

Last blog, we structurally mapped a hypothetical story to see how it worked out. Let’s now look at the questions that came up.

Does the pacing look right, focusing on just a couple of days, then skimming through months?

This suggests that the author has tried to ground their characters as a means of introduction by starting with a new beginning – moving into a new house. As a device, this would probably work well.

The story itself is either about some dissonance the protagonist is experiencing and how they reconcile it in their life, or about this torrid affair that’s going to disrupt the protagonist’s present-day life. It could be a combination of the two, but weighted heavier in the rationale of the former scenario – this seems likely given that, wedding aside, the protagonist continues to reminisce about sad times in her life.

But to get to the disruption (the affair) the author skims through four months of story time. Four months. Why? Probably because the author wants to illustrate that life has become ordinary for the couple as they settle into a routine. Then the protagonist meets somebody, flirts with them, and an affair results.

Unfortunately, nothing in that present-day story of that four months seems particularly meaningful, instead existing to introduce the backstory which is giving us context about the protagonist – she has emotional issues, and these might motivate why she strays later.

So what’s happening is that the narrative becomes weighted in telling backstory, rather than sticking to the current story.

How about the digressions – particularly the one about the father’s funeral, and the parents’ divorce?

Some authors handle digressions well. Others devolve into inexorable backstory.

Exposition is always going to be a necessary evil, but we should fall back on it as a last resort. Also, it’s imperative we avoid talking at the reader, e.g. And this happened, and that happened, and that’s how we got here. Some authors unwittingly put their story on hold to do this so they can arm the reader with the information they require to move forward with the present-day narrative.

The moment you leave your current-day setting/scene, you’re probably producing exposition.

In the case of our graph, the author devolves into an unwieldy and distracting amount of exposition relating to the father’s funeral, and the parents’ divorce. I’m sure the author considers this required to show that the protagonist came from a household where the parents broke up, and the father’s death affected her deeply – possible reasons why she might risk suburban contentment for an affair.

But there really is a lot of this exposition. A lot. Is it all needed? Is there ways we can show this? How could the author show that the parents were divorced? And that her father has died? Simple suggestions are pictures of the father everywhere, which shows she’s close to him, even enshrined him. The separation could come in a single line of dialogue, e.g. ‘I don’t want to end up like my mum and dad, divorced and never moving on.’ Sixteen words, instead of twelve paragraphs – what probably amounts to 700–800 words. This also answers the question, Are there too many digressions?

Alternatively, we might learn about it in a conversation the protagonist has with her mother. E.g.

- Protagonist: ‘Anniversary of Dad’s death this weekend.’

Mother: ‘Have you replaced those tattered curtains yet?’

Thirteen words of dialogue and look at what it shows us: the protagonist is mindful enough of her father’s death that she remembers the anniversary. The mother doesn’t want to speak about him, so she moves onto some inane topic, like the curtains. Either the mother has been so affected by her husband’s death she doesn’t want to talk about him or, likelier, acrimony existed between them and she wants to gloss over it.

Is the timeline complicated or confused?

An interesting point is that the couple was married two years ago, but the protagonist’s miscarriage was four years ago. Did she have a miscarriage with her current partner? Was their relationship that serious then that they planned to have a baby, or was it an accident? If their relationship was that serious, why did they not get married for a further two years? Did she have a miscarriage with somebody else maybe? Or perhaps this is just a changed premise – often, when we’re beginning stories, the details are vague, and they can change as we go on. So maybe this is just an error. But it’s definitely something worth noting.

Does structural mapping help?

If you’re confused about structure, or a novice to writing and are unsure if you’re getting structure right, a structural map is invaluable. It can help identify what’s working, what’s not, and what’s being overplayed. Often, we might not realise this as we’re writing, or (not) spot it as we’re revising because we’re too immersed in the manuscript. But a simple map like the one displayed in the previous blog can chart the forward progress of our narrative, and the backward dips that slow it down, and which amount to a ship dragging an anchor behind it. Otherwise, it might help us identify incongruities.

So think about structural mapping when you revise. It might help you identify issues you otherwise have trouble seeing.