Blog

Welcome to the Busybird blog, where you can find helpful articles, updates, industry news and more. Make sure you stay up to date by signing up to our newsletter below.

Research for Writers

March 6, 2014 This time last year, just about the only writing I was doing was shopping lists and putting my baby’s check-up appointment times into the calendar. As a new mother, writing projects were the last thing I was thinking about. As the year progressed, my attitude towards writing ranged from apathy to frustration at not being able to follow through on my good intentions to write.

This time last year, just about the only writing I was doing was shopping lists and putting my baby’s check-up appointment times into the calendar. As a new mother, writing projects were the last thing I was thinking about. As the year progressed, my attitude towards writing ranged from apathy to frustration at not being able to follow through on my good intentions to write.

I recently attended a workshop with Hazel Edwards. After six hours of discussing various elements of writing and publishing, I asked Hazel what tips she has, having been through this herself, for writers who are mothers of young children. It’s all nice to talk about synopses and pitches to publishers, but how the heck do I get to that stage when I’m at home with a 15 month old?

I was expecting her to say something like, Writers write. You need to make it a priority, even with young children, and write every day and I hoped she might have some magical practical tips on how to do this and still get the family fed and the house cleaned. Her response surprised me, and was refreshingly encouraging.

Firstly, she said to take the pressure off myself. (Really? You’re not going to chastise me for my lack of productivity?) Secondly, and this is what I want to elaborate on, she said to use this time for research. This period of my life – staying home with a baby – won’t last forever, and though I may not be writing much at the moment, there are ways I can use this season to grow as a writer and develop my writing for the future.

As I have thought about the concept of using my life as research, I have come up with the following suggestions. I’ve written them from the point of view as a mother, but these are certainly not aimed solely at new parents and can be adapted for any writer. We all face challenging circumstances at some stage, some of which will prevent us from having the time or energy to write, be it sickness (ourselves or close friends/relatives), changes in work pressures, study that does not lend itself to your writing projects – whatever it is, I hope you find these suggestions helpful in preparing you for the next season of your life when you are able to dedicate more time to writing.

Keep a journal

You don’t need to write in it every day. And you don’t need to show it to anyone else. Journals serve a number of purposes. Firstly, they get you writing. It might not be the same style as your creative writing, but at least it’s getting you thinking of words and stringing together sentences more comprehensive than ‘Ooh, look! Doggy! Woof woof!’ Secondly, it’s a great record of memories, which can be used later to shape your stories. You are able to write more authentically into particular situations, based on your personal experience. It will also be invaluable if you one day choose to write a memoir. Thirdly, journaling is a good habit to get into with therapeutic benefits as you process the joys and challenges of life. (Journals also make great pieces of memorabilia to put in a museum when you become famous.)

Keep a writing journal

Different to your personal journal, this is a notebook where you can scribble anecdotes and ideas (and stick in shopping dockets or used envelopes or whatever else you write sudden bursts of inspiration on) based on your observations of the world around you. Take it with you when you go shopping or on public transport and observe people – this could be the seed for some great characters later on. You might see something strange or humorous that could trigger a storyline, or hear some thought-provoking dialogue. Building up a store of these journals will be well worth the effort later when you’re searching for ideas.

If writing in a journal is too much effort (‘Is there a pen in this house that actually works?’), use a dictaphone (or the recording feature on your phone). Keep it in an easily accessible location such as beside your bed or in your handbag/nappy bag. (Hmm, then again, it could get lost in there.) When you get an idea, you can ramble it off and refer to it later. Plus, it’s easy to use while rocking a baby to sleep. Bub doesn’t care about what you’re saying – she just likes to hear your voice. So rather than get frustrated as you hold her for hours, have your dictaphone handy and talk through your ideas for the next chapter of your novel, or record some dialogue to transcribe later.

Read

As mentioned in previous Busybird blogs, writers need to be readers. So while bub has his nap, curl up with a good book. Or read while feeding. Hey, you’re spending hours a day sitting in your favourite comfy chair anyway, why not spend the time reading? Maybe not hardcovers, should it slip from your grip, but I discovered that I could hold a chunky paperback with one hand and got pretty good at page turns with a dexterous pinky. Reading can also provide a well-earned mental and physical break.

Take photos

A picture tells a thousand words, right? So take a few snaps, write about them later, and there’s a short story. (Sort of.) When you’re out and about, observe your surroundings and take some photos (and try to get some subjects other than your baby). If you want something a bit different to keep your creative juices flowing, use a ‘photo a day’ (or similar – Google it) list for themes/concepts to look out for. You don’t need to have a fancy camera, or be an expert photographer. Just use your phone to capture images that can trigger memories later. The photos you take today just might be the inspiration you need for a really powerful description of setting in the future.

If the circumstances of your life are preventing you from writing, don’t feel frustrated. You can still grow as a writer now. Capture the sights, sounds and emotions in your current experiences and file them away for future reference to inform your writing later.

J.G.

NaNoWriMo Lessons

February 27, 2014 Last October, when my daughter was almost a year old, I decided that after a year of minimal progress on my writing projects, it was time to get back into it. And what better way to throw myself right in than to take on the challenge of NaNoWriMo? (National Novel Writers’ Month = write 50,000 words of your novel during the month of November. Crazy, I know.)

Last October, when my daughter was almost a year old, I decided that after a year of minimal progress on my writing projects, it was time to get back into it. And what better way to throw myself right in than to take on the challenge of NaNoWriMo? (National Novel Writers’ Month = write 50,000 words of your novel during the month of November. Crazy, I know.)

I’ll say up front that I didn’t make it to the 50k, but I learned some useful things along the way. It has been helpful to reflect on these things, months after the event, in order to try and continue to develop as a writer.

An unrealistic goal is better than no goal

It is good to have achievable goals to motivate you and help you track your progress. But, as I found, it can be good to sometimes take on a really ambitious goal to help push you forward. I knew that trying to write 50,000 words in a month was going to be tough. Even if I was already consistently writing and didn’t have a baby to look after it would be a challenge. Add to that a family holiday interstate, my brother’s wedding and planning a first birthday party. I knew that November was a really inconvenient time to try this and felt that if I made it to 50,000 I could pretty much do anything as a writer.

As it turned out, I stopped after a couple of weeks so I could focus on my family commitments. I could have the attitude of, Wow, I didn’t even make it halfway and feel like a failure. Instead, I think to myself, Wow! I wrote over 20,000 words in two weeks! Had I not had such a lofty goal, I would not have achieved as much as I did.

The fact that I didn’t reach my target has not put me off wanting to try again. I’m excited to give it another shot, and am looking forward to Camp NaNo, held in July.

Get words down

I have often heard quotes along the lines of ‘You can’t edit nothing.’ It’s true. There’s no point having a great idea if it stays in your head. It’s not until you get it down on paper or onto your computer that you can start working with it, crafting the words into something amazing. NaNoWriMo taught me to keep writing and moving forward. There’s time to edit later, but just get that first draft done. This is not how I usually write. I’m an editor, and like to edit my work as I go. I go for quality over quantity and cringe over moving on from an imperfect sentence. In the first few days of NaNo, I felt uncomfortable about not revisiting my work straight away. But I soon felt a liberation in trying something new and just writing and letting the words flow (and seeing the word count ticking over).

Value the writing community

The third point I want to make about NaNo is the importance of being part of a writing community. Writing is a solitary activity, but writers need not feel isolated. One reason for my lack of productivity last year in writing is that I was not proactive in surrounding myself with other writers. I didn’t have deadlines to complete any of my writing projects, I didn’t have anyone encouraging me/kicking me up the butt to keep going and I didn’t have anyone giving feedback on my work. I didn’t realise how valuable these things are until I no longer had them. For the two years prior, I studied Professional Writing and Editing and this year have decided to study once again – not just in order to finish my Diploma, but also for the benefit of workshopping and being inspired by other writers.

Each day during November I was receiving emails with pep talks from authors and updates on how others were going with NaNoWriMo. I didn’t meet any of them face to face, but there was something motivational about knowing I was not in this alone – there were thousands of other writers taking on the same challenge.

Whether online or in person, get a group of writers around you. Do a writing course, or contact your local library or writers’ centre to find a suitable writers’ group for mutual encouragement.

J.G.

The Delicate Relationship

February 20, 2014 Writing is a solitary profession … right? You wake up each day, write, and at some indeterminate point in the future, you shape the story, shake out the dead leaves and stand back from your marvellous, topiary-like creation, with a growing feeling of confidence that it is complete. It’s ready for publishing.

Writing is a solitary profession … right? You wake up each day, write, and at some indeterminate point in the future, you shape the story, shake out the dead leaves and stand back from your marvellous, topiary-like creation, with a growing feeling of confidence that it is complete. It’s ready for publishing.

But it isn’t. You are not the painter, whose work is finished when they deem it so. Nobody tapped on Picasso’s shoulder and said, ‘I think your proportions are a bit off.’ You are much more like the film-maker or musician, despite the obvious differences between these mediums. There is a need for further opinion, a need for collaboration, a need for … editing.

Say your story is selected to be published in a literary journal. You receive an email full of praise. You feel proud and think you might be pretty good at this writing caper. You entertain fantasies of quitting your day job.

Just as you’ve finished a mental list of things you’ll spend your royalties on when you inevitably become a best-selling author, some horrible, Grinch-like intern sends your story back to you. You click open the file with a shaky hand. The document has corrections in a confronting shade of red; little comment bubbles in the margin with suggestions for improvement; and a cover letter asking you to consider changes to the opus you’ve spent weeks, if not months, moulding into a masterpiece.

The buzz of being accepted for publication is killed. Part of you is confused: they said your story was wonderful, Vonnegut-esque, inspired! What could possibly have possessed them to edit your story!?

The truth is your work has been chosen for any number of reasons – but rarely is it chosen because it’s perfect. Your favourite author had/has an editor, and you will too. That’s how the business works. More importantly, your story is a representation of the journal it appears in, so great care is taken by the publisher to elevate it to the highest standard possible. Writers are not the only ones who want to look good in the eyes of the literary community.

When submitting your work, you are entering into an unspoken agreement that (unless otherwise stated) your work will be edited, whether it be a little or a lot. Take comfort in the fact that the people who selected your story saw great potential in it and only seek to enhance its existing great qualities. Adjust your attitude and this necessary process will be far less painful. Know that you are not powerless, either: you decide, ultimately, how the final draft reads. Changes aren’t arbitrary, either. You can discuss them with your editor, argue your point, or compromise.

The editor’s aim is not to stifle the writer’s voice, but to clarify language and make your work as strong as possible. And, unlike film editors and music producers, prose editors get no credit. As far as the reader is concerned, your writing is as brilliant as the published version, and not a draft sooner.

That’s kind of cool, isn’t it?

While I have some experience editing for (and being edited by) friends, my first proper opportunity to work with an author on [untitled] was a positive one. This writer was open to suggestions, justified their decision to retain certain word choices or phrasing, and was courteous in correspondence. Over several months we took an already promising story, sanded back the rough edges and polished it until it sparkled. I’m confident it is fantastic now. More importantly, so does the author.

No story, just like no human being, is beyond improvement. Approaching the delicate relationship with an editor with an open mind and willingness to bring the best out of your work will go a long way towards bettering your writing, and bettering yourself as a writer.

H.K.

A Lofty Goal

February 13, 2014![[untitled] issue six has arrived!](https://www.busybird.com.au/app/uploads/2014/02/untitledissuesixes-e1392263274348.jpg)

A lot of work goes into putting together [untitled]. We have interns who plough through (hundreds of) submissions, we have regular content meetings to discuss the merit of stories, there’s editing (which will go on until we’re all satisfied – possibly, to the occasional chagrin of the author), copyediting, several rounds of proofreading, layout, cover design and printing.

[untitled] is not a (financially) profitable venture either, although it would be awesome if it did become one – not just for our benefit, but because it would mean that it’s evolved beyond being a little journal. It’s become a legitimate book anthology that’s selling to the masses.

That’s an interesting distinction between journal and book, despite their physical similarities. An author releases a collection of short stories, it’s a book. A publisher releases a themed collection of short stories from different authors, it’s also a book. But we (or any other small publisher) release an anthology of short stories garnered through a slushpile by authors who are still new and emerging, it’s a journal (or something equivalent).

Perhaps another (albeit unspoken) distinction are their target audiences. Books are released to the greater public. People who have no interest in being writers themselves and who simply enjoy reading will buy a book. But journals are largely read by other writers. Some journals will even stipulate that they only accept unsolicited submissions from subscribers, which I guess keeps them in that cycle, like the snake swallowing its own tail.

We want to be a book (also), though, damnit. That’s our goal. We want [untitled] to sit comfortably in bookstores, that the market – whether it’s other writers or simply readers – will recognise [untitled] as that little paperback that can always be relied on to contain great stories. A lofty goal, but also a worthwhile one.

We also hope [untitled] continues to give new and emerging writers exposure. There’s a lot of great writers around the country who are discouraged by rejection, or sometimes struggle to find homes for their stories. Go through most journals, and you’ll be able to identify a distinctive style as to what they’re looking for. Go through [untitled] and, hopefully, you won’t be able to identify anything thematically, or in regards to a specific type of prose, but stories that have been chosen regardless of their shape, size, intent, but but because they are great stories.

As an aside, there is also [untitled]‘s short story competition to consider, which closes 15th February (Saturday, so online submissions should be open until Sunday, and we’ll accept hardcopy of anything postmarked no later than the 15th). So, if you’re interested, the details for our competition can be found here (and that page contains details of how to submit in hardcopy) or you can go directly to submitting online by clicking here.

In any case, we celebrate the launch of [untitled] issue six on Wednesday, 19th February, beginning at 7.00pm. This also coincides with the return of Open Mic Night. So whether you just want to be a participant or a part of the audience, come along for what’s sure to be a great night.

Hope to see you there.

LZ.

Approaching Revision — Part II

February 6, 2014The Big Picture

Last week, we looked at a lot of the mechanics of writing which you can address during revision. This week, we’re going to look at the bigger picture – your story as a whole.

Last week, we looked at a lot of the mechanics of writing which you can address during revision. This week, we’re going to look at the bigger picture – your story as a whole.

Whatever your story, it will create a set of laws that govern that story’s universe. If we’re writing contemporary drama, that’s not so important, because we’re subject to the laws of everyday life – unless we incorporate something supernatural (e.g. vampires) or magical (e.g. wizards). Then we need to work out how those beings function in our society, and what laws govern them. If we’ve written sci fi, we may need to consider the physics of the universe, e.g. how fast does a ship travel, how much damage can it take in battle? If we’ve written fantasy, our universe may be populated by magic and amazing creatures, such as dragons and serpents. If a character is capable of magic, we need to determine how their magic works and when and how it can be used.

You need to know the answers to these questions when you’re writing. These laws will govern the behaviours of your characters. It’ll also create an airtight universe which won’t insult or lose the reader with inconsistencies – and readers will pick these things up. These questions themselves may never be exhibited in the story itself, but they are the framework that shapes your world, dictates causality and defines your characters’ boundaries.

There are also other obvious questions that you can ask once you’ve finished your piece, such as:

-

Is the plot sound?

As in does it make sense and there are no holes in it that would be exposed by an astute reader?

Are the characters three-dimensional?

We all have our strengths, weaknesses, desires, peeves, et al. Our characters also need to have them – particularly if you’re writing villains. Villains shouldn’t be evil for the sake of being evil. Characters should also have arcs, an evolution that occurs over the course of the story.

Is the logic of your story motivated and are the motivations of your story logical?

Characters need believable motivation for why they take the action they do. None of us do things without reasons. If your character burns down the neighbour’s house, is it believable that they would take this action? And is it believable what pushed them to this action? A neighbour might play loud music all night, every night for a month. Would that trigger you into burning their house down? Maybe not. What if your character had an ill child and the child died because they just couldn’t get the rest to recuperate? Well, that might push your character over the edge.

Are subplots and supporting characters attended?

Writing can be difficult when we’re juggling and trying to keep so many things and so many people in the air at once. It can be very easy to drop a few, forget about them, and pick them up only when they’ve been all but forgotten.

Something useful when writing a longer work, such as a book, is to diagram the book in a graph so you can get an overview of the structure.

Before we proceed with that, let’s create a hypothetical novel we can work on: Bob is a 20-year-old student at university. He has a girlfriend named Lisa, although her ex Greg is not happy about their relationship and keeps trying to win Lisa back. Bob lives in a flat with his best friend Henry. They struggle to pay the rent, although Bob works after school and weekends in a pet store. When the university is robbed, Bob is incriminated and charged. He then has to clear his name.

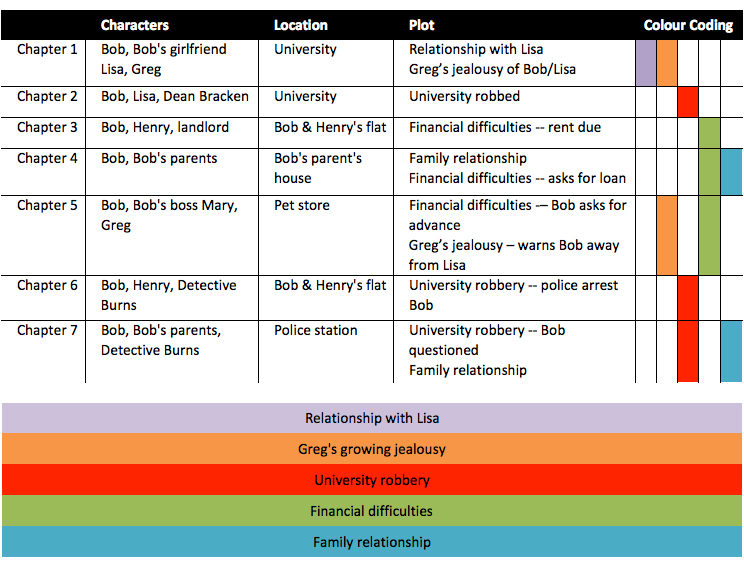

Okay, it’s a very simple idea, but exists solely for the exercise of our diagram. In our diagram, we’d have several columns, which would list which chapter it is, the characters who appear in that chapter, the location (or locations) used in that chapter, as well as which plots and subplots have been attended. If we wanted to be really fancy (and we will, for the sake of this exercise) we could attribute a colour to each plot, and list that, too.

What we’re left with might look like this:

At a glance, we can now see how our book is unfolding, what characters and plots are being attended, and what’s being neglected.

Just from a glance, Bob’s financial difficulties dominates the story, which may be considered repetitive. Do we really need all that happening at once? Lisa appears at the beginning, and then is unsighted. Perhaps we can include her elsewhere – how about in Chapter 6, when the police come to arrest Bob? Maybe Bob and Lisa are having a romantic dinner. That would further their relationship, but also add drama since Lisa will be witness to Bob’s arrest. Henry, whilst in the book so far, doesn’t seem to feature in any storyline. Is he actually required?

This is a basic example but it does give us an overview to demonstrate how useful story diagramming can be as a tool when we revise.

LZ.