In life, we’re always accumulating knowledge. We accumulate it through what we read, what we watch, the people we interact with, our experiences, our successes, and our failures. We are, for the most part, knowledge-gaining machines when you consider that we start off our lives only really knowing that we should cry when we’re uncomfortable or insecure.

We also gain knowledge from some of the unlikeliest sources. Did you know it takes the average human seven minutes to fall asleep? I read that in a Stephen King novel decades ago – I don’t recall the novel, but I’ve always remembered that fact. We are surrounded by information. It comes in various forms and titbits, regardless of the vehicle.

Some of it becomes essential to us personally or professionally. All the knowledge I’d gain at home in working with computers, software like Word, and online platforms such as WordPress, I was able to take into work. When I was developing this knowledge base, I didn’t realise how useful it would become to me in a professional environment. I thought I was just screwing around.

Sometimes, information seems either surplus to our needs, or just plain old unnecessary. When we die, how much stuff will we know which we never used, was never useful, and/or had no real merit in our lives? Learning it took seven minutes for the average human to fall asleep was – if nothing else – an interesting titbit.

Many would argue that contemporary schooling is replete with lessons that are not germane to real life. Back in Year 9, one history teacher (who eventually became principal of our school) insisted we memorise every state in the USA. As a 14-year-old living in Melbourne, Australia, I didn’t understand the relevance. Similarly with classes such as Legal Studies and Accounting. If I’m ever up on a murder charge, it’s not like I’ll defend myself because I took Year 9 Legal Studies.

Of course, some of these classes exist only to broaden our minds in directions they may not have gone otherwise. Additionally, they’re there to act as tasters. For some, they might be the platform to pursuing careers in these fields – for some. There’s a key phrase, though. It gets you thinking: what do we learn in life that would seem essential for all?

The answer is simple: writing.

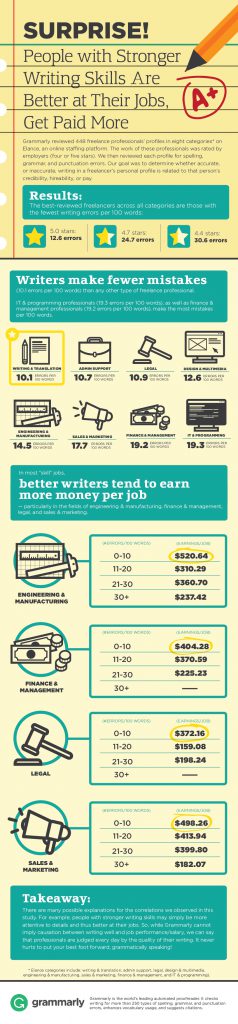

The good people at Grammarly have allowed us to repost the image you see running alongside this blog, which studies how people with stronger writing skills are ‘are better at their jobs, [and] get paid more’. Take a look at the image (you can expand it by clicking on it) and note the differential in errors between professions, as well as salaries.

Grammarly concludes:

There are many possible explanations for the correlations we observed in this study. For example, people with stronger writing skills may simply be more attentive to details and thus better at their jobs. So, while Grammarly cannot imply causation between writing well and job/performance salary, we can say that professionals are judged every day by the quality of their writing. It never hurts to put your best foot forward, grammatically speaking!

Writing well requires something else, though: innovation.

Writers operate in a constant state of innovation. We consider the perfect word, pursue the perfect phrasing, write and rewrite ourselves in our heads before we even get a letter down on the page, and then we revise ourselves on the page. Writing well is, in fact, both a state of high achievement, and improving on everything we’ve done before.

So are the benefits any surprise?

Thanks again to Nikolas Baron and Grammarly.

LZ.