Busybird

Welcome to the Busybird blog, where you can find helpful articles, updates, industry news and more. Make sure you stay up to date by signing up to our newsletter below.

The Hard Work of Writing

October 26, 2017Tonight, we’re off to a launch!

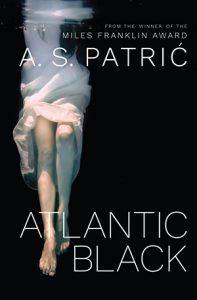

A.S. Patrić, an alumni of Busybird’s short story anthologies 13 Stories and [untitled] issue 2, and author of Black Rock, White City – the winner of the 2016 Miles Franklin – will be launching his new book, Atlantic Black.

A.S. Patrić, an alumni of Busybird’s short story anthologies 13 Stories and [untitled] issue 2, and author of Black Rock, White City – the winner of the 2016 Miles Franklin – will be launching his new book, Atlantic Black.

Set on an ocean liner, the Aquitania, Atlantic Black tells the story of seventeen-year-old Katerina Klova, who must navigate Aquitania and the guests and crew aboard after her mother suffers a psychotic breakdown. We were privileged to read an advance copy, and it’s a stunning and haunting book. Set over a single day leading into New Year’s Eve 1939, you can feel how painstakingly Patrić has crafted every paragraph, sculpted every sentence, and handpicked every word.

This is something a lot of people – especially people who aren’t writers, or aren’t in any way involved in the writing industry – don’t understand: writing takes a lot of work. Most wouldn’t think so. Most would believe it’s a case of sitting at the keyboard, spilling out your imagination (and that process is apparently immediate), and then having a book at the end of it. There. Done. No problem. No revision. No editing. Nothing like that. The book emerges fully formed.

Let’s do some basic maths – and here, I’m going to err generously on the side of the uninitiated.

A novel might, on average, be 80,000 words.

A writer might, on average, pound out 500 words per half hour (and this is extremely generous).

80,000 / 500 = 160.

That’s 160 hours a writer needs to produce a book.

Let’s break this down further: most writers would have a life going on outside their writing – they may be married and have kids, and on top of that they may be working a full-time job; even if they’re single, they’re likely to be working or studying. Everybody has commitments – professional, personal, and familial.

Hypothetically, this person might wake at 7.00am, go through their morning routine (breakfast, showering, etc.), then get to work around 9.00. Even desk jobs sitting at a computer are tiring – for some, they can be even more tiring, because they’re occupying the same physical space they would as a writer. They work until 5.00, and might not get home until almost 6.00. They then have to make dinner and wash up, so are on the go until 7.00. The evening for the writer with kids will be brimming with responsibilities like homework, dinner, washing up, etc. – depending on the age of the kids, they might need to be supervised. The single writer has more space, but will have their own demands. Whatever the circumstances, at some point, the writer will have to sit down and write.

Let me backstep again to qualify this is erring so generously on everything going right – from how much time they have available to write, to how many words the writer produces, to what they write being usable – that it’s fantastical. Because things don’t go right. The writer might have not slept well, they might have had a tough day at work, unforeseen problems might crop up that take their time and attention. Any of a number of things can happen to derail their efforts to write. And yet they still have to do it. On top of all this, how good is what they’re writing? It might be terrible. It might need revision. It might not fit and have to be discarded. It’s a constant grind of trying to get it all just good enough to finish the damned thing, and then move to the next stage – revision.

Writers will revise extensively. They might have readers who provide feedback on early drafts. More revision follows. If they’re submitting to publishers, they need to prepare synopsises and cover letters – and most writers struggle with diluting their writing into one-page form. If they have a publishing contract, they’ll have structural and then copyediting feedback to attend. Another 80 hours isn’t unrealistic (and, again, errs generously on the side of things going right).

It’s a lot of work, trying to realise a vision their imagination has provided, and articulate it in a way that’ll make sense (i.e. produce a suspension of disbelief), create the universe their story occupies, and engage a reader. And you’ll never please everybody – that’s reality. Just check Goodreads and see the way ratings fluctuate. Most writers who’ve been at their craft for years are wracked with insecurity, knowing everything that could be wrong or could go wrong with their book. They’ll strive to eliminate all those potentialities, yet will obsess over how well they’ve done.

Writing is hard. Anybody who thinks it’s easy doesn’t understand what’s required. Or they’re an idiot. Either way, they don’t appreciate writing as a practice and the work that goes into it. Kudos to those who seriously pursue the undertaking. Even more plaudits to those who finish something.

This is why launches are important – they’re a way to celebrate all that labour and commerorate a book’s arrival into the world.

If you’re in attendance, or follow a writer’s page, let them know how much you appreciate the work they put in.

It’s not easy. It’s never easy. And it should be lauded.

How I Used the Busybird Creative Fellowship: Angus Watson

October 12, 2017

When I applied for the Busybird Creative Fellowship, I had just finished the first draft of my novel. I didn’t know much about styles, grammar, or even the industry.

But I had a 90,000-word novel, which I thought the world of.

I attended Busybird’s Open Mic nights (I urge everybody to do the same, even if you don’t want to read!) which provided a nurturing environment. I was encouraged by everyone I met, and so decided to put my name forward for a year of mentoring, a hot desk, and free attendance to in-house workshops.

In December 2015, I was granted the 2016 Busybird Creative Fellowship.

By January 2016, the 90,000 words of my novel had turned into 40,000.

This wasn’t done as one might expect, through vicious slashing and personal loss as characters ceased to exist, but rather by learning how to better tell my story. Even though I had cut more than half the word count, I had enhanced the overall story arc, smoothened the flow, and made my characters more real and interesting. It was still my story. I learned how to do all this and more through the mentoring of Busybird’s staff and the many in-depth workshops they run.

At the end of the Fellowship, my skills had increased, yes, but what I found equally valuable, was that I now had conviction. How to improve my writing. What the next step was. And where I realistically wanted to aim.

Using Busybird’s contacts, I have since started a writing group functioning at the Eltham Library. We meet regularly to workshop and provide feedback on each other’s writing, discuss our projects, and help one another grow.

I wouldn’t have had the confidence or contacts to facilitate such a writing group, nor the skills and knowledge to be a contributing member. The Busybird Fellowship has created a solid base for where I hope my writing might take me, and I encourage everyone considering applying to do so!

The Different Forms of Publishing

October 5, 2017The publishing landscape is always evolving but, despite this, the fundamentals remain the same. If you’re interested in publishing, you can try and get ‘traditionally published’ or, if you want to do it yourself, you can ‘self-publish’. Then, you have what are called ‘partnership publishers’ – publishers who claim they will share the cost and risk of publishing your book. Before exploring each route further, let’s look at what they involve:

Traditional Publishing

A traditional publisher will take on all the financial obligations of publishing your book. You will not pay a cent.

A traditional publisher will take on all the financial obligations of publishing your book. You will not pay a cent.

How it works …

- You will submit a sample of your manuscript to a publisher. Every publisher will have different guidelines as to what they want to see. But usually, it’s something like the first three chapters of your book, a synopsis, and a cover letter. For nonfiction, they may also want a market breakdown, i.e. you’ll be asked to provide similar titles to yours on the market.

- Every publisher has different response times. About three months is normal.

- If they’re not interested, you’ll receive a rejection, although it’s becoming common now that no response after a certain time equals a rejection.

- If they’re interested, they’ll ask to see the rest of the book.

- Again, you’ll wait. Times vary.

- If they’re not interested, you’ll receive a rejection. Because you’ve come this far, they might personalise the rejection and offer feedback.

- If they’re interested, they’ll offer you a contract.

- The contract will be to print your book and will include:

- The publisher’s obligation to take on the editing of the book.

- This publisher will provide a ‘structural’ edit, where they offer feedback, and explain where they believe your book needs work. You may go back and forth with the publisher several times to get the book to a standard you’re both happy with.

- Then comes the ‘copy’ edit, which looks at the text line by line and addresses grammar, punctuation, spelling, and clarity of expression. Small publishers might have the same editor provide the structural and copy edit. Bigger publishers may have different editors performing these tasks.

- The book will go to a designer, who will provide the layout.

- The designer will work on a cover. While the publisher and the designer will consider your input as to what you believe the cover will look like, they will have a better idea about what’s suitable for your book and how it will fit into the market.

- The publisher’s obligation to take on the editing of the book.

- The manuscript will be sent to a proofreader, who’ll give it a last going over. This is usually a fresh set of eyes. They will also be looking for any issues the layout might have introduced, e.g. the loss of manual formatting (such as italics for emphasis), or headings that might’ve been swallowed into the text.

- Financially, the contract will offer:

- Royalties – about 10% of every book sold (so, a couple of bucks for every copy).

- An advance, which is a set amount of money. This usually won’t be a very big figure.

Or: - An advance against royalties, which means your royalties will have to pay off the advance before you see any further money.

- The contract will be to print your book and will include:

- The publisher will have your book printed. The print run depends on how saleable they believe your book is. Big publishers might ordinarily publish 2,000 copies for a first-time author.

- The publisher will distribute the book, e.g. get it in bookstores.

- The publisher will try to organise marketing for you and your book, e.g. interviews and reviews.

For a lot of people, being published ‘traditionally’ is about validation – it’s about a publisher decreeing your work is good enough to be published commercially and bear their name.

Self-Publishing

You pay for whatever services you require to publish your book. You then try and get it in bookstores yourself.

You pay for whatever services you require to publish your book. You then try and get it in bookstores yourself.

A lot of people skimp on what’s required to self publish – we can’t count the amount of times somebody has told us their book doesn’t need editing because they’ve had somebody who has some experience with English (e.g. a Year 9 English teacher) read the book.

It’s up to you to determine what you need, but if you’re going to self-publish it’s worth doing it right and putting your book through the same wringer a traditional publisher would. Don’t ever believe that the strength of your content as a whole will override poor punctuation, misspellings, or a shoddy layout. It won’t. It’ll just make your book look unprofessional.

This is largely why self-publishing once had a stigma attached to it – your book wasn’t good enough to publish traditionally, so you did it yourself, and did a slipshod job. Then you have a chicken-and-the-egg situation: is your book bad because it’s self-published, or did you self-publish because it’s bad?

Self publishing has become accessible due to the evolution of technology, particularly in the realms of print-on-demand (where you can print as little as one copy of your book) or ebook publishing. In terms of hardcopy, you can publish a book that’s indistinguishable from books coming out of the big multinational publishers, e.g. Penguin, Allen & Unwin, Hachette.

A number of self-published authors have done well, e.g. Andy Weir with The Martian (adapted to film, starring Matt Damon); Lisa Genova with Still Alice (adapted to film, starring Julianne Moore and Alec Baldwin); and Amanda Hocking, who published paranormal romance as ebooks annually (on Amazon), was hugely successful, and then picked up by a traditional publisher.

If you self-publish, you should retain all your profits (minus expenses).

Should. Some self publishers might want to claim some portion of your royalties and rights. Do not surrender these.

As Blaise says, the moment you pay as little as one dollar to publish, you’re self-publishing, and deserve the full return for your labours. Sure, pay for services. Haggle if you need to. But keep 100% of your rights and 100% of your royalties. In self-publishing, you effectively become your own publisher.

There are other legitimate stakeholders that do come into the picture, though, e.g. bookstores and distributors: bookstores will take 40% for every book sold (of the RRP), and distributors (an organisation hired to get your book in bookstores) will take 30%.

Partnership Publishing

You and the publisher (supposedly) split the cost of publishing your book fifty/fifty.

You and the publisher (supposedly) split the cost of publishing your book fifty/fifty.

- You submit to a publisher, or pay for a manuscript assessment.

- They rave about your manuscript and offer to publish, under an ‘innovative’ contract model.

- You undertake much of the route you would with a traditional publisher.

- Instead of going to print, they may print a ‘galley’ copy (just a printout) and distribute it for review.

- Reviews will be glorious.

- The partnership publisher will try to convince you, based on the strength of the reviews, that you publish. Print runs may be exorbitant, e.g. 3,000 copies.

Most partnership publishers are unscrupulous – we can’t attest to them all, but the ones we know of (through clients who’ve been burned, and come to us) are shameless.

They will flatter you and gush over your manuscript. They’ll tell you that you have a bestseller, that the market is just waiting for a book like yours. As a writer, your ego will be satiated.

The partnership publisher will convince you to publish, claiming they’ll split costs with you, which means you get to share the profits 50/50. In actuality, they probably don’t put a cent in towards the development of your manuscript. You’ll be paying entirely, while they outsource needs (e.g. editing, design) to subcontractors. The subcontractors will do their best, given that this is their livelihood, but they’ll be paid (low) flat rates and be given limited turnarounds.

The reality is ‘partnership publishing’ is just self publishing, but using a middleman to oversee the process – a middleman who’ll lay claim to your royalties (as well as rights to your book) despite having no investment whatsoever in it. The least investment they’ll have in it is a personal or emotional investment. You at least want somebody who genuinely believes in your manuscript.

If you think you’re looking at a traditional publisher, but they ask you to put money in, you’re actually dealing with a partnership publisher. Often, you won’t be able to tell because they have the transparency of mud. You’d be much better self-publishing with people who are upfront.

At Busybird, we’re always interested in educating and nursing authors, and making sure they have a pleasurable and rewarding publishing journey, so we hope this breakdown has been helpful.

There are the three realms of publishing – two viable, and the other to stay clear away from!

Responsible Reviewing

September 21, 2017 The internet has given everybody a voice.

The internet has given everybody a voice.

It’s also provided numerous mediums in which to use it.

One of those mediums is the forum of critique – reviewing books, movies, etc.

Art will always be interpreted subjectively. You don’t need to love – or even like – something just because other people do. That’s fine – we all have different tastes. But criticism should be valid, justifiable, and constructive. Unfortunately, this often isn’t the case. It’s surprising the amount of biased reviews that are out there – reviews driven by a personal agenda.

So what exactly are we looking at?

Okay, let’s look at reviews as they apply to books (although this could easily extend to other mediums of art) …

- The Troll Review

Somebody is scathing just for the sake of driving a reaction. Often, the troll review will be outrageous, as it will try to provoke responses. There’s no merit in this review. If you can recognize the troll, stay away. Don’t feed it.

The ‘Witty’ Deconstruction

An analysis using humour (particularly acerbic humour) that dissects the book. The dissection itself could have merit, but it seems the reviewer wants to prove how funny and incisive they can be. While some might laud these reviews, if you really stop to think about them, you’ll see that they can be mean-spirited and cruel – sometimes, without the reviewer even realizing it themselves. It’s tantamount to ridicule.

The ‘I Don’t Get It’

Somebody reviews something they’d never read recreationally, and then criticizes it on the basis that they don’t get it, or it hasn’t piqued their interest. It’s like giving a historical romance to somebody who specializes in science fiction. Reviewers should abstain from reviewing something if they don’t feel they can invest in it for what it is. It shouldn’t start so far back because the reviewer doesn’t like that particular genre.

The Misinterpretation

Close behind the ‘I Don’t Get it’ is the reviewer who misinterprets the book – be it a scene, scenes, or the whole book – and then criticizes it through a raft of misapprehensions. If you’ve read the book these reviews are bashing, you might frown, and think, No, that’s not what happened at all! But the reviewer has misunderstood, misread, or misinterpreted what’s going on; or is clueless and attacks as a diversion from realising their own cluelessness.

The Early Abandonment

Somebody reads only a small portion of a book, can’t get into it for whatever reason, then flicks it. That’s fine as a practice, but it’s not a good foundation for a review. A review should be of the material as a whole, because who knows what might’ve happened the page after the book was abandoned? A review which reads, I read fifty pages but couldn’t get into it so I dumped it. One star might’ve been, if the whole book was read, A slow beginning evolves into a compelling thriller! Three stars.

Undoubtedly, there’s hybrids of these reviews, but these are the principles of bad reviewing, and these examples should give you an idea of how they’re unfair on material, and not judging it on its merit. This is not to excuse bad writing. It’s out there. But too many reviews criticise through the filter of some prejudice – intentionally or not – as these examples demonstrate.

Whenever you critique anything, you need to try empathise with the author’s intent, understand where they’re trying to get to, and then look at what’s working and not working in achieving those objectives. If something’s not working, the criticism needs to transcend personal taste, e.g. I didn’t like this character because he was stupid. Maybe that character’s meant to be stupid, so is that criticism valid? But if the character was stupid, and his actions unbelievable, that could warrant criticism.

If you’re going to write a review – particularly a negative review – think about how you would feel if you received that review, and that should give you a good indication of whether you’re being fair and balanced or not.