Busybird

Welcome to the Busybird blog, where you can find helpful articles, updates, industry news and more. Make sure you stay up to date by signing up to our newsletter below.

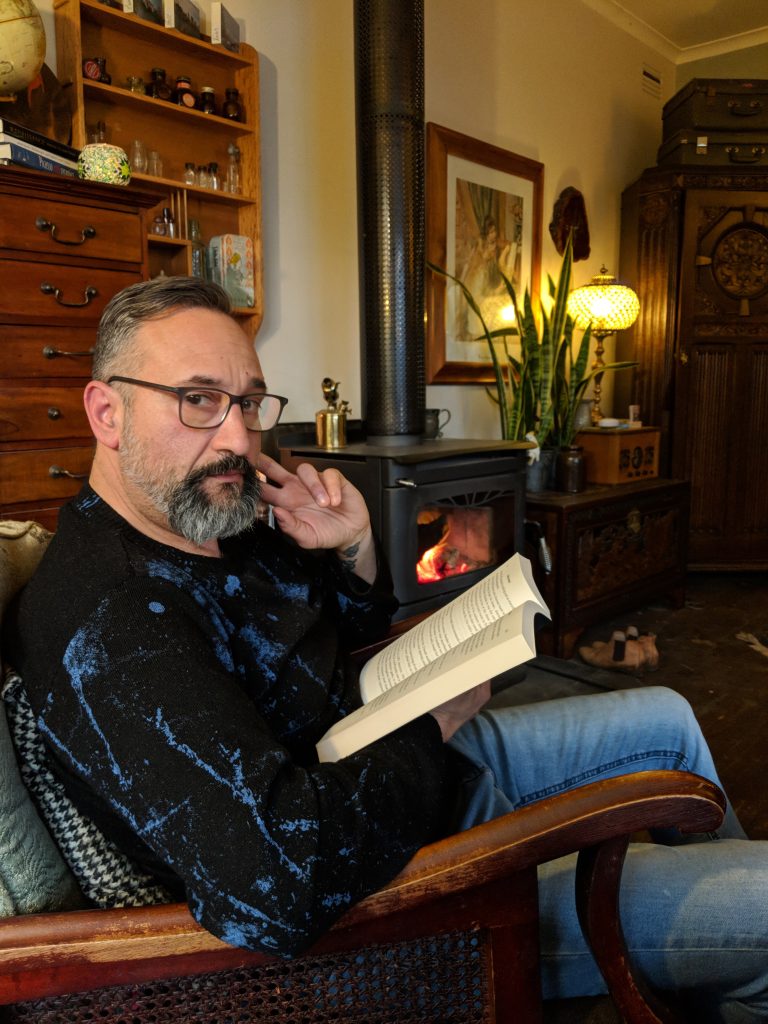

Profile: Con Shalevski

April 11, 2023

Tell us a bit about yourself …

My name is Con and I have been writing since high school back in 1984. This is the first book I have published and I’m so excited to keep doing so.

I’m also a professional wrestler and have been since 1996. I have done some stage acting and I’ve been an extra in many shows, including Neighbours and Rush.

I’m passionate about books and everything that comes with it, but writing sits there on top.

What draws you to writing?

Creating a story and characters would have to be the most interesting part of writing. It all needs to be put in a way where readers can follow and understand.

My ideas over the years have proven to be just that, and now I have the opportunity to bring them to life in a book.

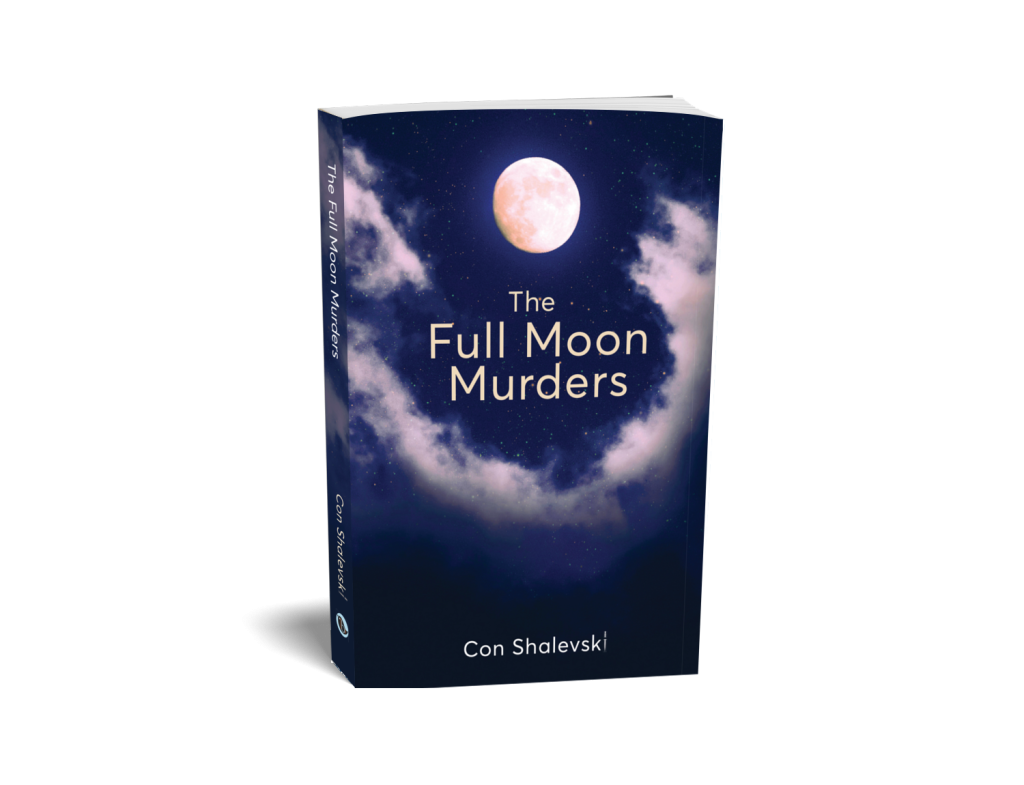

So tell us about your book?

The idea for The Full Moon Murders originally came from a play I had written in school for drama class. Before the play could be performed, the drama teacher decided to change schools and nothing ever generated after that.

I sat on this script for over thirty-five years and now we have this book with the same characters and storyline as the play.

Two detectives team up with an American student whose friend ends up being one of the victims. Annie fears for her life so she gets close to one of the detectives and tries to help out where she can. A chase around Victoria and NSW finds them all in harm’s way. The twist at the end will leave everyone with their mouth open.

Where did the idea come from?

I am infatuated with serial killers and murder. I try to recreate events on what they could possibly be thinking. I try to put myself in their shoes.

Crime/Thriller is the only genre I want to write – well, at least for now.

What’s the story you’re trying to tell?

Murder is not cut straight murder. See what I did there? There are so many ways to kill a person and I will demonstrate that in the books I will write.

And what do you hope your readers draw from your writing?

A new found love and passion for murder mysteries. I have fresh and unique stories that I want to share with all the readers.

What’s your writing process?

I create the idea for the next book while I’m writing the one before. I have a little writing pad that I carry with me everywhere I go. I write down ideas as they pop in my head. I then work out a rough finish to work with and start my story from there.

Tell us one thing about your book, or your writing process, that nobody else knows.

Each chapter gets written there and there on the spot. The ideas flow while I write.

If I’m blank for a period – longer than five minutes – I close the lap-top and try again the next day.

I have multiple stories floating in my head and I need to sort through them for the one I need then.

What are you working on next?

My next book I’m releasing is called The Invitation.

It’s three stories about an event that is attached to The Invitation and what could go wrong at this event.

Is there suspense? Sure. Is it a thrilling, nail biting story? You bet.

Is there murder? One-hundred percent.

When readers talk about you as an author, what do you hope they’re saying?

A fresh and new look in serial killing. More psychotic, more deranged, a lot more unpredictable. I want to show everyone my talented, dangerous and warped mind in storytelling.

Any advice for other writers?

Never stop thinking, never stop writing. Life is a story and we all want to hear a new one.

Follow your dreams and ideas until you have what you’re searching for.

Where can we get your book?

My book, The Full Moon Murders is currently sold online at Amazon, Booktopia and Book Depository. The Book Barn in Belgrave has copies and The Patch General Store sells copies too.

Or, if you want a signed copy, please private message me on messenger and I’ll be more than happy to personally sign it and mail it out to you.

Links:

Find me on my Instagram account: conshalevski_theauthor

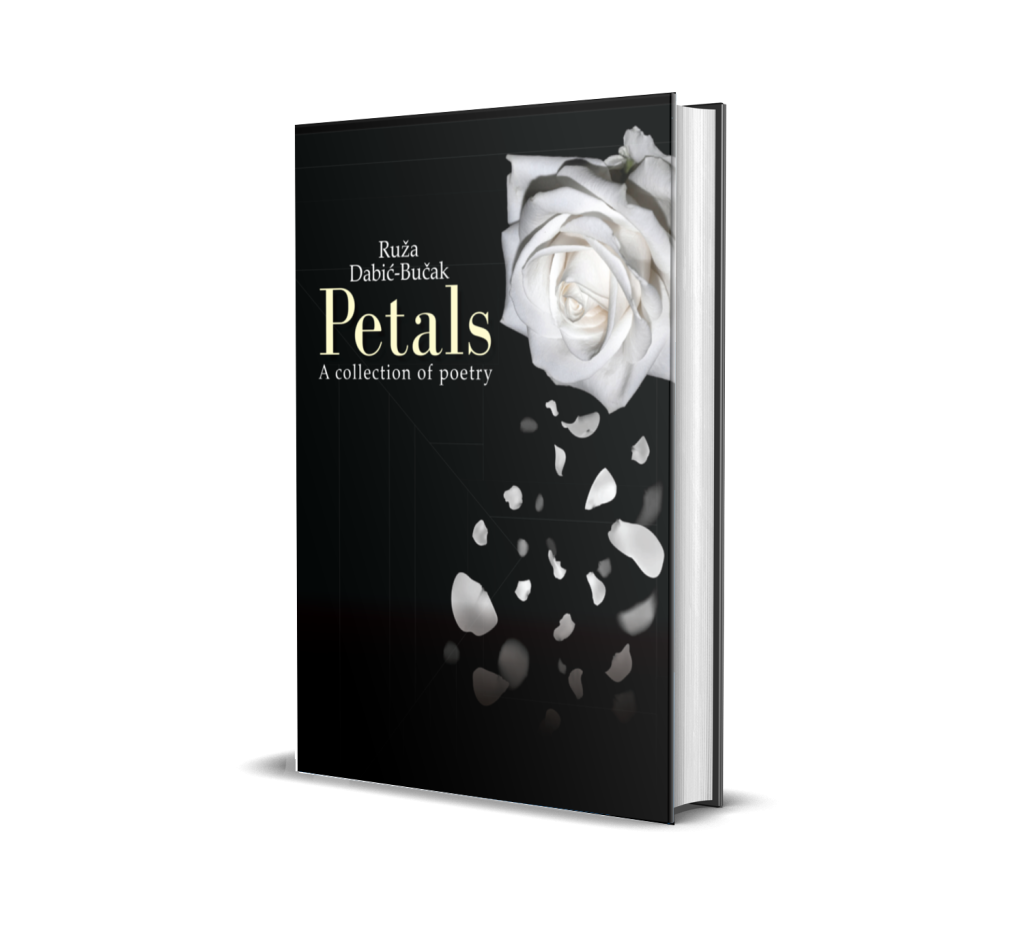

Profile: Ruža Dabić-Bučak

April 4, 2023

Tell us a bit about yourself …

My name is Ruža Dabić-Bučak. I was born in Croatia in 1950 and grew up in my much loved Kolonija-Šećerana, Županja. My husband and I immigrated to Melbourne, Australia, in 1971, where we still live with our two children and three grandchildren.

What draws you to writing?

With writing I create a desired picture with words. I never plan to write. This feeling comes to me and insists that I write. Writing is necessary to me, like the sun, air, food and water.

So tell us about your book …

I write in Croatian and English. My poems are mostly autobiographical, the rest comes from my thoughts and feelings. I wrote this book in English so that my children and grandchildren and future generations will always know where and what they come from. My story is a picture of a moment in history that created new bloodline. Each of my poems is a petal from a moment in my life.

And what do you hope your readers draw from your writing?

I hope that my readers feel something – anything – of what I felt writing my poems.

What’s your writing process?

My inspirations come to me at the most inopportune times: as I am falling to sleep, driving a car, watching a movie. They dictate the language in which I am to write that poem. Usually I don’t stop till work is done.

I still write by hand. It’s pen, paper and me. We are the A-Team. Only when my work is revised many times, I type and file it.

Tell us one thing about your book, or your writing process, that nobody else knows.

If I get stuck I shut my eyes and see the way out.

What are you working on next?

At present I am working on four different pieces, two in English and two in Croatian.

When readers talk about you as an author, what do you hope they’re saying?

If readers talk about me as an author I hope they would say, “She is original.”

Any advice for other writers?

To other writers, I would say to follow your heart.

Where can we get your book?

Through me, Busybird Publishing, or Amazon.

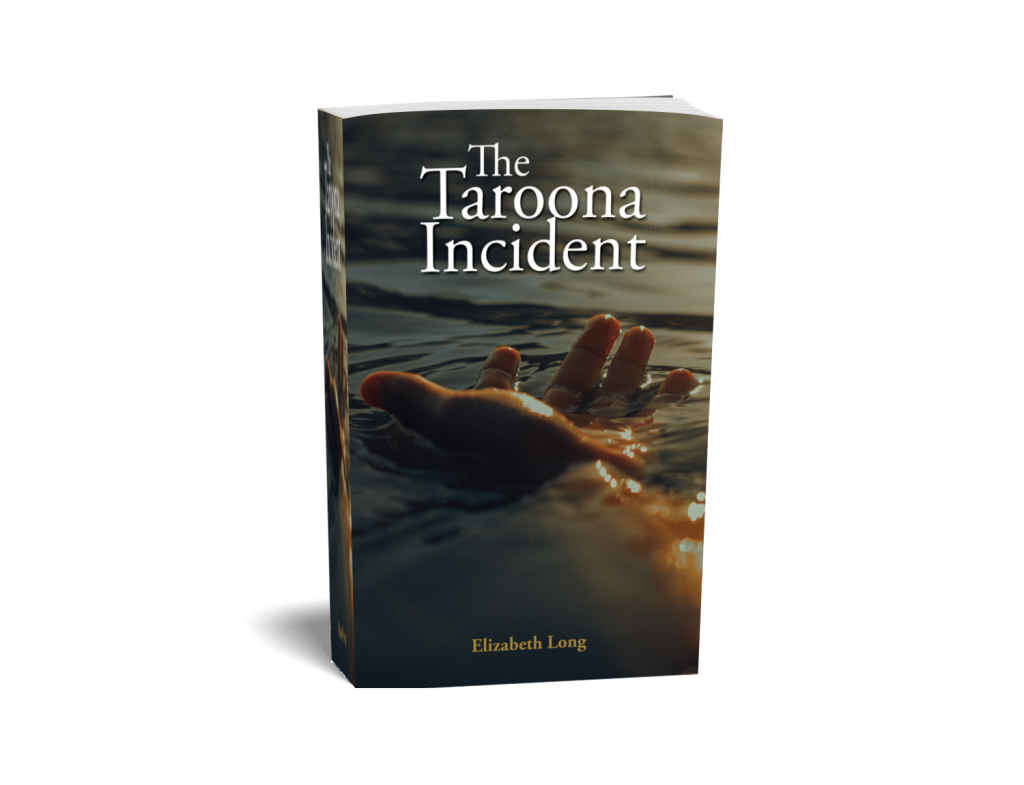

Profile: Elizabeth Long

March 28, 2023

Tell us a bit about yourself.

I was born in Tasmania and came to Melbourne at the age of 18, just for a visit. Most Tasmanians used to call it the ‘Big Smoke’. That very title spoke to me as a place of intrigue and excitement. I was off. I came to like Melbourne very much, secured a job and stayed.

What draws you to writing?

Like a lot of authors (I assume) I love writing and have done it since secondary school where I received high distinctions for my essays. Added to that I find it easier to write things down than say them (if that makes sense).

So tell us about your book?

My first book is about something terrible that happened to an ordinary hard-working family.

It begins at a time when people didn’t necessary lock their doors and children played all day until they were called for tea. No one worried about where they were. It was a different time then. The story progresses to the 1990s.

Where did the idea come from?

It simply came into my mind as a what if?

How did it happen, why did it happen and what would be the consequences?

What’s the story you’re trying to tell?

How family support each other. How friends gather around those they love. Why some family members hold grudges. It’s also about resilience and justice.

And what do you hope your readers draw from your writing?

A reader wrote back to me recently and spoke about how they felt about my book.

They said they really enjoyed it. ‘The twists were unexpected’, and the story ‘tugged there heart strings on several occasions’ and made them cry.

That is exactly what I hoped my story would bring to readers.

What’s your writing process?

Firstly, when I have settled on some of the plot (it evolves along the way) I make notes about the characters. Things like their age, where they come from, what are their relationships with each other. I settle on names during that process as well.

Tell us one thing about your book, or your writing process, that nobody else knows.

Sometimes I become frustrated. It doesn’t always flow for me. I need to take a walk and clear my mind. I can also spend a lot of time on research which is very time consuming when really. I just want to get on with it.

What are you working on next?

‘A Body in the Lane’, which is a spinoff from my first book, The Taroona Incident. A few characters make a reappearance but it is a completely different story.

When readers talk about you as an author, what do you hope they’re saying?

I hope they say I tell a good yarn, they enjoyed it, the characters and settings were well described and they were surprised by the ending.

Any advice for other writers?

I’m not sure I’m that practiced at writing to advise.

However, I do think you should have an idea of what you want to say. Make notes first and get to know your characters before you begin. Don’t be afraid to change direction if it’s not working. Be prepared for some frustration at times. It’s not always easy.

Where can people find your book?

I do have hard copies if anyone wants to buy directly. I’m also on most eBook platforms. such as, Amazon, Booktopia, Barnes and Noble and others.

Please include any social media links you want to share.

I’m on Facebook and Goodreads. Or, please refer to the publisher for other contact details

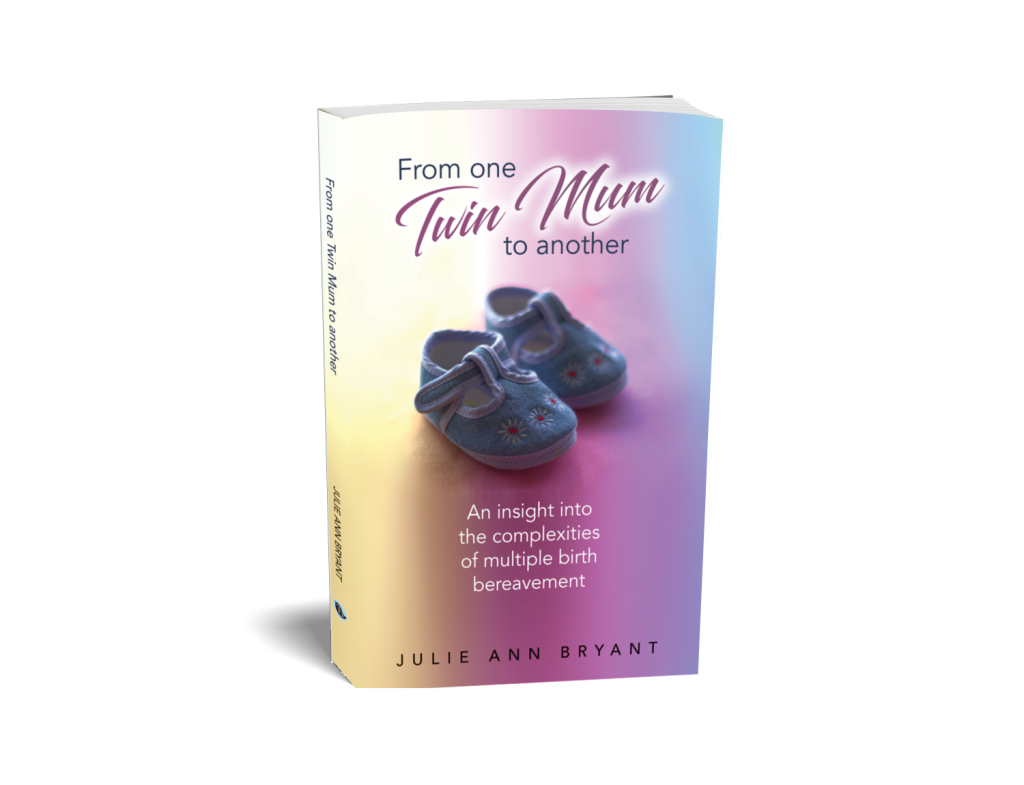

Profile: Julie Ann Bryant

March 21, 2023Tell us a bit about yourself.

Hi, I am Julie Ann and together with my husband and our two adult children, I live in the Illawarra NSW – a region traditionally known as Dharawal Country, the land of the Wodi Wodi people. I work from home as a medical transcriptionist in radiology.

When my children were young, I completed the Advanced Diploma of Applied Social Science.

My studies focused on grief and loss, and I have a specific interest in disenfranchised grief, especially as it relates to multiple birth bereavement.

My other interests include listening to music, writing poetry and nature photography.

What draws you to writing?

I am a visual thinker and have always expressed myself through writing. I began writing poetry in my teenage years. Consequently, it was a natural progression for me to keep journals through the years. Now, since publishing my book, I am also adding to my webpage blog week-by-week.

There is something about seeing words materialise in black and white in front of me on the screen that helps my thoughts develop. For me, writing (in whatever form) is an opportunity to tell my story, in my own words, in my own way and at my own pace.

Writing provides me with a safe haven in which to explore my thoughts, process experiences and draw on insights that I can learn from going forward. It is also a process that I find quite cathartic.

So tell us about your book …

My book is called From One Twin Mum To Another and it is my first published work, inspired by my experience in 2001 of a complicated, high-risk IVF twin pregnancy.

I use the word inspired quite deliberately because it is not a memoir. As a very private person, I felt more comfortable writing in the setting of psychology/self-help.

My book is intended as a guide, firstly, for newly bereaved multiple-birth parents as well as their social supports and their professional supports.

There is a strong emphasis on being self-aware about mental wellbeing in the context of grief and considers various aspects of support, self-care and creating something of personal meaning out of the loss.

Where did the idea come from?

One morning in May last year I woke with the thought, Today is the day I start writing my book.

As random as that thought was, I decided to run with it and see what might eventuate. Within six months, my book was written, proofed and published.

As for writing in my chosen genres of nonfiction/psychology/self-help, I have always been drawn to memoirs and autobiographies. There is something about understanding the experiences and insights of other people that resonates a lot with me.

What’s the story you’re trying to tell?

My message about grief is that it is:

- Firstly, complex and we need to have a good support network around us.

- Secondly, a necessary process that we work through for our long-term mental wellbeing.

- Thirdly, survivable – as overwhelming as it feels in the first few years following a significant loss, but as we change through the years, so too will our grief.

Having an unborn baby die has a profound impact on the expectant parents.

When that loss occurs in the context of a twin pregnancy, it is still a loss that needs to be acknowledged and grieved.

And what do you hope your readers draw from your writing?

In my introduction I wrote, “I want to reach out to you through the pages of this book to reassure you that you will get through this”.

I hope my book conveys that no matter how unusual their circumstance of twin loss feels, that they are not alone and they will survive their grief.

Whilst not a memoir, I have shared my insights from my twin pregnancy to provide information to my readers that I hope will be of great relevance and significance for them personally.

What’s your writing process?

When it came to researching for my book, a lot of my personal research included looking through the many things I had written through the years. Some of those writings dated back over twenty years and were adapted for Chapter One; Similarly, I adapted other old writings dating back some ten years for Chapter Two.

Of course, I also conducted research further afield at various points in writing my book.

When my living children were of preschool age, my psychology studies provided an opportunity to examine in depth the more complicated forms of loss and grief.

Conducting that research and composing each of the ninety-six essays was a wonderful learning experience in itself, which I am sure served to prepare me well in advance for writing my book.

My natural style of writing has always been to “free associate” my thoughts and that is certainly how I approach writing poetry and journals. This is also how I initially approached writing the book as well. With any concept in my mind, I would write what I knew and continue writing as much as I could.

I bought an A4 lecture book and every day scribbled thoughts into it, thoughts that would run in the background of my mind as I worked on the manuscript. I also had a pen and notepad at my bedside for those random 3am thoughts!

Once I had the bones of the first four chapters, I wrote, researched, rewrote and read out loud what I had written thus far and continued this process … sometimes several times over, slowing fleshing it all out.

Towards the end of my draft manuscript, I took a week off work and each day that week, I read my manuscript out loud, cover-to-cover. Whenever something didn’t sound quite right, I would go back and rework that part until it flowed.

By the fifth day and the fifth time I had read the manuscript out loud, it sounded and felt the way I had originally intended. That was when I was confident my manuscript was ready to hand over for proofing and subsequently also, publishing.

In researching, seeking permission from other authors, etc, I decided that it would be easier to just use my own original poetry – that way I didn’t need to seek permission to publish the work of other poets.

Likewise with the cover images, I used my own photos – again so that I didn’t have to seek permission to use the work of another photographer.

Tell us one thing about your book, or your writing process, that nobody else knows.

I must admit, this question had me stumped for a few days.

And then, in looking through my table of contents I realised a parallel between Worden’s “Four Tasks Of Mourning” (as mentioned in my Preface) and the first four chapters of my book. Obviously, this was not intentional during the stages of my writing, but very much a happy coincidence for me!

Worden’s first task of mourning is to accept the reality of the death and my first chapter looks at the complexity of life and death in a twin pregnancy and in contexts such as the prenatal appointments and creating a birth plan for both babies.

The second task of mourning is to feel the pain of that realisation and my second chapter examines what grief looks like through the eyes of the grieving parents.

The third task is to adjust to life in the face of the loss and my third chapter considers the support networks the grieving parents need to gather around them, as they slowly adjust in terms of their grief, and as they parent their newborn surviving twin.

The fourth task is to memorialise your loved one. One of the main points of my fourth chapter is that the parents create something of personal meaning out of their loss that they can carry with them as they move forward with their lives.

What are you working on next?

I am still working on this book, or at least, getting it out there – and it is in my thinking this year to create an audiobook.

A few weeks ago I hand-delivered a copy of my book to a young twin mum who lives in my neighbourhood.

As we sat on her lounge talking and playing with her surviving twin daughter, I glanced across the room to see her mother sitting in an armchair, my book open in her hands, quietly engrossed in reading.

The memory of that image makes my heart sing.

I really want for my book to find its way to where it needs to be – in the hands of grieving twin parents, as well as their social supports and professional supports.

As the writing of my book all happened within the space of six months, now I am playing catch up – making contact far and wide with health and mental health professionals who may, one day, have bereaved multiple birth parents in their care and, thus, may benefit from the information my book provides.

Who knows what my next writing project will be? Maybe one morning, I will just wake up and know that something new and exciting is about to begin …

When readers talk about you as an author, what do you hope they’re saying?

Firstly, that I have approached a complex and little understood area of pregnancy loss and presented it in a comprehensive way.

Secondly, that I have written in such a way as to invite everyone into the conversation about multiple birth bereavement, thus opening up the opportunity to talk about loss, grief, the importance of good mental wellbeing and of feeling well supported, both socially and professionally.

Any advice for other writers?

Believe in the message you are trying to tell. Be passionate about telling it.

For those times when writer’s block has you staring at a blank screen for any length of time, find a way to push through and tell that story anyway. Free associate your thoughts and you may find that this becomes your best piece of writing simply because you put more time, thought and effort into making it happen.

Finally, do you want to promote your book (where people can buy it) or any events where you might be featuring?

BRYANT, Julie Ann. From One Twin Mum To Another: An insight into the complexities of multiple birth bereavement. (2022) Melbourne: Busybird Publishing

My book can be bought direct from myself and I am happy to provide a signed copy on request. There is an order form for this on my website.

My book is also widely available online in both paperback and ebook formats and, again, I have provided links on my web page to the more well-known online stores, such as: Amazon, Booktopia, Angus & Robertson, Bookshop, Fishpond, Book Depository, Blackwells, Barnes and Noble, Walmart, etc.

My blogs can be read at the following links:

My website – https://fromonetwinmumtoanother.com/blog/

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/julieannbryant.author/

Twitter – https://twitter.com/OneTwinMum

Our Loss

March 14, 2023Preface: This is a piece that Joe Dolce – Blaise’s stepfather, her ‘Dad Plus One’ as she called him – wrote shortly after her passing, and which we’re publishing to commemorate the first-year anniversary of her passing.

The 2 am call to me from her husband, the dread of telling her mother the horrific news, the anxious drive to the Austin Hospital, still half-asleep, the long wait in the hospital parking lot with her sons and their partners (COVID rules), her mother finally allowed in, with the husband, the rest of us much later, watching her quietly lying on the hospital gurney, on a ventilator, unsure what to do, the necessary drive back home to await the brain specialist, the CT scan, the numbing drive back to the hospital, the gathering in the waiting room with her older sister, her older brother (whom we haven’t spoken to in seven years, the embrace and emotional reconciliation), the crushing news that it was hopeless to operate (catastrophic brain bleed), the decision to turn off the machines, the nurse reading through organ donation forms, a final farewell to her and heartbreak of listening to her mother whispering close to her, as though she could hear, how much she loved her, the leaving her behind, the silent drive home, the knowledge life-support was turned off, the reality of loss hitting us over the next days, her mother, in the bath, weeping that she couldn’t go on, the desperate embraces at night, the intermittent and interrupted sleeps, the planning of the funeral, at first, no idea how to proceed, the service to be held at Montsalvat Colony, the choosing of the cardboard coffin (her wish), the idea for her youngest son to paint it, his trepidation that he wasn’t able (too much grief), his grandmother’s encouragement and offer to work beside him, adding flowers, the unforeseen dental emergency requiring her to have antibiotics and rest, the decision to let her grandson complete the painting alone, his brilliant achievement, the drive to Montsalvat to inspect the venue, the preparations: catering, printed programs, live video feed, photographic slideshow, order of eulogies and social media invitations, the late morning drive on the day for the ceremony, her husband’s uncertainty whether anyone would come, the hall filling with an endless stream of family and friends, the gaily painted coffin covered in freshly-cut flowers, the moving service, her sister, husband and two sons speaking through their weeping, the fine measured talk by the esteemed author (a last minute addition), the reading of May Swenson’s The Key to Everything, her mother’s wonderful stories and memories with her, her oldest son’s wife’s unexpected but memorable recitation from the daughter’s final book, The Road to Tralfamadore is Bathed in River Water, the wheeling of the coffin out into the sunny courtyard, the guests writing short messages on the box, the utterly perfect day, the furious bellbirds chiming, her coffin stripped of flowers carried to the hearse and driven away, the tea, cut sandwiches and scones in the long hall, the emotional goodbyes, the long slow drive, back home, exhausted, the days upon days following with intermittent tears and joyful recollections, of the lost daughter, that never end.

– Joe Dolce.