Blog

Welcome to the Busybird blog, where you can find helpful articles, updates, industry news and more. Make sure you stay up to date by signing up to our newsletter below.

Our New Website

August 15, 2019

We have a new website! It’s been a long time coming, but here it is!

One of the reasons we felt we needed a change is because we’ve just got so much going on. Between publishing our own books (under our imprint of Pinion Press); helping authors to get their own stories out there through self-publishing; individual services such as manuscript assessments, editing, proofreading, etc.; workshops; retreats; Open Mic Night; blogging; and so much more, our old website had begun to buckle under the strain of trying to accommodate, promote, and deal with it all.

Every time something new came up, we either had to work out where it fit, or rejig the whole website to give it a home. For example, our blog went from its own page, to sitting under Author Resources. The reason? Because we wanted to give away Freebies, such as pdfs to Map Out Your Book and Test Your Book Concept (with more to come). This blog itself tries to be a resource in educating writers. There’s also the subscription to our newsletter. So instead of those things being individualised, they were grouped together.

Our new website has been designed to incorporate everything we offer, from books to services to events. There is omnipresent immediate access to all the important stuff. And it’s aesthetically prettier than the old website. With our old website, we were winging it ourselves, doing the best we could. With the new website, we’ve retained professional web developers.

However, this new website isn’t entirely finished. A lot the copy was transferred across from the original website, and some punctuation characters came out weird, appearing as Ð, Õ, among other things. Some images came across fine. Others became blurry. These are all little teething problems that we’re aware of, and will work to correct in coming weeks.

But, because of this, we’re extending the deadline of our Eggcellent Manuscript Assessment Competition. Unfortunately, when we were transitioning from one the old website to the new, the competition page was lost, so writers couldn’t find the competition details and the entry form. We now have a new page up, along with a new entry form, and the new deadline of 15th September.

Seeing you’re here, have a look around. Let us know what you think.

We’ll be officially recognising the website as launched at Open Mic Night this Wednesday, 21st August, beginning (as always) at 7.00pm.

We hope to see you all there!

The Value of a Manuscript Assessment

August 1, 2019 Authors often comes to us, asking what means they could employ to improve their manuscript.

Authors often comes to us, asking what means they could employ to improve their manuscript.

There’s editing, which would look at the manuscript in terms of structure or copy (or a combination of both).

There are also workshops, although they’re designed more to improve the writer’s skills, which they will then apply to their manuscript.

A lesser-known but equally valid means is a manuscript assessment.

Usually, the authors stare blankly back at us. We try to explain that the assessment is like a book report. Usually, they still frown at us.

Here’s a basic breakdown of what you’re going to see in a manuscript assessment:

- A look at the title: does it work? Does it encapsulate the book? Is the title too common? Is it already in use? You may not have considered any of this, married to a title you thought was perfect. Or you might have a placeholder, and you’re unsure what title would encapsulate the book.

- Point of View: does your manuscript’s POV work? Are you flitting in and out of different POVs? How do POVs work anyway?

- Plot / Content: if it’s a novel, how does the plot work? Is it sound? Does it build the story as intended? Does it introduce stakes? If it’s nonfiction, does the content communicate its message? Whether it’s fiction or nonfiction, does the writing achieve what it sets out to do? If not, why not? What can the author look at in terms of improving it?

- Structure: is the information delivered in the best way possible? Could it work better a different way? Is it underwritten or overwritten? Does it build logically?

- Punctuation, Grammar, Spelling: self-explanatory – a look at what you might be doing wrong and an explanation on how to correct it.

- Characterisations: in regards to a novel, a review of the characters. Are they well-formed? Are they believable and motivated?

- Market: where does your book sit in the market? If you haven’t considered this, the assessment can help you identify where you should be pitching your manuscript, or how to reframe it so you can place it in the market.

- Conclusion: summing up your manuscript.

Now, obviously, the assessment won’t cite every single instance of an issue. For example, if your POV is jumping around, the assessment won’t list every place it’s happening. It will explain how it’s jumping around and give you a handful of examples, educating you on what to look out for. That’s the same case with anything that might be occurring regularly.

The plot/content and structural feedback will be much more specific about what a manuscript needs. It can also open an author’s eyes to what they’ve been – or become – blind to. But that’s understandable. After working on a manuscript for so long, it’s normal that authors will lose objectivity. That’s where fresh eyes help.

And that’s why a manuscript assessment is invaluable. It’s great to get feedback from family, friends, etc., but a manuscript assessment is written by somebody who is trained to spot these issues and articulate methods to correct them.

A manuscript assessment is a priceless and an inexpensive insight.

Postscript: Don’t forget that our Eggcellent Manuscript Assessment Competition is on!

Anthologies

July 18, 2019 The anthology – as a concept – doesn’t get the acclaim it truly deserves.

The anthology – as a concept – doesn’t get the acclaim it truly deserves.

A single-authored anthology allows that author to explore different forms and different subjects. It gives the reader a chance to see the author experiment. That doesn’t necessarily happen with a book. A book might be (for example) a third-person linear narrative told in past-tense and that’s it. That’s the vehicle. An anthology doesn’t have those restrictions, because every piece can be different.

Great examples with prose are Ryan O’Neill’s The Weight of the Human Heart, A. S. Patrić’s The Butcherbird Stories, or Julie Koh’s Portable Curiosities. These authors are able to flex their storytelling muscle and play with form. As a reader, it can be challenging, entertaining and immersive. As a writer reading somebody else’s work, it’s educating as well.

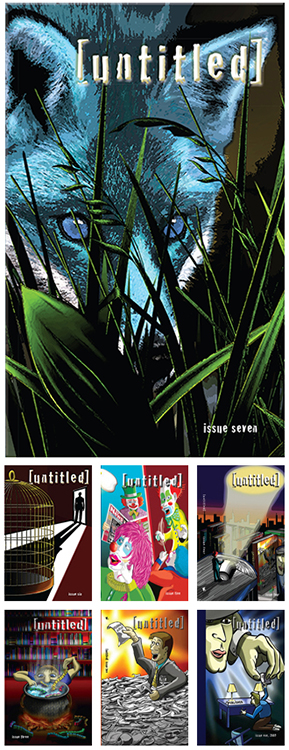

Anthologies are also fantastic mediums to discover and explore new and emerging talent. Our very own [untitled] is a perfect example. Early issues published authors such as Ryan O’Neill, A. S. Patrić, Emilie Collyer, Koraly Dimitriadis, Laurie Steed, Tess Evans, George Ivanoff, and many more – writers who’ve built (and continue to build) careers as authors in one form or another. Did we make their careers? No. But we’d like to think we contributed to their development, their exposure, and encouragement to keep writing.

As a prose author, anthologies can be a good way to start putting writing out there. They can seem hard to crack into, and arbitrary in their decision-making, but as somebody who’s been involved in various anthologies, I can tell you lots of talk goes into deciding which stories go through.

Sometimes, rejections aren’t due to quality, but …

- space constraints, e.g. here’s a great 4,000-word story, but we’ve projected we have only 2,000 words remaining we want to fill

- because we have a similar story, e.g. you submit a brilliant story about killer clowns, but we’ve just accepted a story about killer mimes

- it might not fit the tone, e.g. it might be a grim story in a happy anthology, or we might have enough grim content and are now looking at something happy as a counterbalance.

Nonfiction anthologies can also be compelling for similar reasons. We have our HealthConscious series, which (currently) features three books: Healthy Mind, Healthy Body, and Healthy Spirit. Each book looks at maintaining that facet of health filtered through the modality of that author’s vocation, i.e. obviously a psychologist, a naturopath, and a writer are all going to have a different outlook on how to maintain healthiness. This gives you different perspectives on the same topic.

We’ve also done anthologies on breast cancer, prostate cancer, and succeeding in small business, as well as helping various groups publish collections about things such as (just to name a few) a particular historic period (the Great War) or community (the Greensborough historical society) or a particular place (the Balwyn tennis club). Here you get people’s different experiences and stories.

You might not connect with a book for whatever reason. But with anthologies, one story might not connect with you while another does. That’s the beauty of an anthology. They have a widespread appeal and diverse content that is sure to offer something for everybody.

Respecting the Craft

July 4, 2019When talking to people at parties, usually one question is always asked: ‘What do you do?’

Now here’s how these conversations never turn out:

Now here’s how these conversations never turn out:

Person #1: ‘I’m a brain surgeon.’

Person #2: ‘Really? I’ve got an idea for a brain surgery I’d like to try one day.’

Person #1: ‘I’m in bomb disposal.’

Person #2: ‘That’s such a coincidence! I’ve always wanted to disarm a bomb.’

Person #1: ‘I’m a financial adviser.’

Person #2: ‘You don’t say? I’ve always felt I’ve had a knack for financial advice. I’m going to advise somebody one day where to invest all their money.’

Person #1: ‘I’m a nuclear physicist.’

Person #2: ‘Oh, too easy! If I ever get the time, I want to run a nuclear plant.’

Person #1: ‘I’m a serial killer.’

Person #2: ‘It’s like you read my mind! You can’t imagine the people I’m planning to lop off one day!’

You never hear stuff like this because nobody trivialises anybody else’s vocation or passion. They respect that those vocations have required education, training, and practice, or that this passion is is something the speaker has nurtured and cultivated.

Do lay-people think that about writing?

Nope.

A lot of people believe to write a book, all you need to do is sit down and write. That’s it. And what emerges is this fully formed, perfectly written book. This is all it takes, because how hard can it be to make shit up? Or to break down your area of expertise into an actionable methodology? Or to condense somebody’s life into a story? Or to talk with authority about a particular topic? Or to write a book full of verse?

Good writing looks effortless because an author has put countless hours of hard work into it. They do this so you don’t stumble over the prose, or query the punctuation or grammar, or stop and frown about some element of the content. Good writing is like riding a train. You never think about the tracks. You never think about who’s laid them. You don’t ever question the journey. You just sit back and go from beginning to end. Bad writing is like a bumpy ride with frequent unplanned stops and several crashes thrown in. Most people wouldn’t want to take that trip.

There are a lot of good writing courses, retreats, and workshops out there that can help the aspiring writer. These are awesome because you’re surrounded by like-minded people, and your development is fast-tracked because you have people teaching you things that it might otherwise take you years to discover for yourself.

But there are things you can pick up on your own if you’re mindful.

When you’re reading a book, look at the grammar. Most of us speak correctly, but that doesn’t always translate in writing. Then strange idiosyncrasies creep in. Take apart how things work, and look at why they work.

Observe punctuation. It always stuns me when I see people employing numerous …………………… as an ellipsis. It’s three full stops … That’s it. That’s all you will ever see it in print. But while people see it, they don’t record it.

For fiction, when reading, or watching television or movies, examine how the story is put together. We usually get to know the people, something happens, they go on an adventure, and there’s a big climax. If you’re writing bio, dissect how documentaries work – how they build their history from the ground-up to fit a specific journey. If you’re writing self-help, look at how successful authors break down their methodology. As a poet, deconstruct how good poetry works. It’s not just rhymes. There’s more to it than that.

Look around. There are plenty of lessons in everyday life to develop your craft.

But respect that it’s a craft, and do everything to develop it.

The Competition Game

June 20, 2019 Competitions are exciting. We all want to be recognised. We want our work to be lauded. We want that celebration to spread across the publishing industry and consumer market and let people know we (and our work) exist.

Competitions are exciting. We all want to be recognised. We want our work to be lauded. We want that celebration to spread across the publishing industry and consumer market and let people know we (and our work) exist.

We want to mean something.

Then you have the practical output: competitions can lead to goodies, like publication (yay), prize money (yay), mentorships (yay), or even a combination of any or all those. Each one of those things is a boost to any writer’s career. Even the lower prizes can mean something. Being shortlisted and/or longlisted is recognition – encouragement that your work is thereabouts. You’re being told this by people in the industry that it means something.

So that’s all that’s good and wondrous. But competitions can have drawbacks, too.

There are a lot of bad competitions out there.

Shysters thrive in publishing. And why? Because many writers are inexperienced and trusting. Along comes Shyster X: Here’s an opportunity and it costs you this MUCH money. It’s the way this industry works! And does the poor unsuspecting writer know any better? No. So they buy in thinking this is the way things work. (This is why we run workshops on publishing – we want to educate authors.)

The same applies to competitions. It doesn’t take any merit to run a competition. I could start a competition tomorrow, call it The Super Awesome Marvellous Magnificent Book Competition, slap on an entry fee, promise a few prizes, and advertise it, and I’ll get entrants.

For some of these comps, they don’t care about the author. It’s about making money for themselves.

So how can you tell the shysters?

Look at the entry fee.

Is it big? Big entry fees don’t necessarily mean a competition is a scam. There are legitimate competitions that charge $100 per entry (although that’s the maximum I would pay, and these comps are for novel-length works). But keep in mind what you’re being charged, and then …

Look at the prize(s).

What are they offering? A certificate and announcement of your triumph in their media? Well, is that worth their entry fee? I would suggest not. They actually cost the competition zero dollars, zero resources, and very little time and effort to award. The only way I’d consider this meritorious is if the organisation running the competition had serious marquee.

The Text Prize (run by Text Publishing) charges $100 entry, but the winner is published, and gets $10,000 (against the royalties). Affirm Press run a competition in conjunction with Varuna; entry is $100, and the winner is mentored for a year with the hope that their manuscript will be brought to a publishable quality. They’re awesome prizes, and definitely worth their entry fee. Hachette’s Richell Prize (currently open) doesn’t even charge a fee, and yet the winner receives a year of mentoring with the possibility of publication at the end.

Seriously think about whether the prize is worth the entry fee.

Look at the judges.

Imagine submitting a horror novel to a competition that was being judged by Stephen King. Wow. That would be awesome. Competitions often boast about who their judge is because it usually is some acclaimed author. It’s a selling point. Also, you’d like to believe that having a credible author legitimises a competition. Certainly, name authors wouldn’t want to be associated with anything shonky.

But some competitions claim that they have esteemed judges but can’t reveal their identity, or just don’t mention who the judges are at all.

In the case of competitions like those already listed (above), it’s no big thing because the prizes are so great. Your work would no doubt be judged by staff within those publishers who have expertise in their field and are looking for manuscripts to publish and authors to make part of their stable.

If the prize isn’t publication or money or mentoring, if it’s only acclaim, then I’d want to know who was making those judgements. Is it somebody worthwhile (e.g. a well-known author, or some recognised publisher with twenty years’ experience), or some work experience kid? If I’m not told, why are those identities kept secret? Immediately, I’d think it’s because there’s no valid judging process.

Google the competition.

The internet is an amazing place. If you’ve ever had any sort of problem – personal, professional, technical – there’s a very good chance somebody else has encountered it before you and written about it on the internet, or filmed a video that’s up on YouTube.

Competitions are no different. Message boards exist where people talk about competitions. There are sites dedicated to listing credible competitions and those you should stay away from. It’s not hard to research pedigree and validity.

A Google search doesn’t take long, and can save you time, money, and energy in the long run.

It’s not just one thing.

Just one flag isn’t necessarily an issue. A competition might have a hefty entry fee, but offer great prizes. There’s your value. A competition might only offer a small financial prize, but also only have a small entry fee. That’s fair. A competition might have a reasonable entry fee, not much in the way of material prizes, but it’s being judged by an author you love, or a respected publisher. Well, that’s cool.

Look at what’s being offered and ask if you’re getting value for your entry fee, if the prize is worth it, and if the people involved legitimise the competition.

Don’t let your ego be your guide.