Blog

Welcome to the Busybird blog, where you can find helpful articles, updates, industry news and more. Make sure you stay up to date by signing up to our newsletter below.

Characters

March 26, 2015 The relationship between writers and the characters they create is often a tangled one. While not all of us are going to become as entangled with our characters as the lead from Ruby Sparks, it’s often hard to separate ourselves from the voices and personalities we create. Every character, after all, is a reflection of our own perspectives, our own selves – whether it be ourselves, the antithesis of ourselves, or a model of someone else based on our point of view of them.

The relationship between writers and the characters they create is often a tangled one. While not all of us are going to become as entangled with our characters as the lead from Ruby Sparks, it’s often hard to separate ourselves from the voices and personalities we create. Every character, after all, is a reflection of our own perspectives, our own selves – whether it be ourselves, the antithesis of ourselves, or a model of someone else based on our point of view of them.

When characters are the product of a single mind, it can be difficult to make them into convincing individuals – to take them further than just being mouthpieces of ourselves, with different hats on. So how can that be done?

It can take a long development to reach that stage. But here’s some general tips to making your characters more than caricatures.

Read as widely as possible

One to get under your belt before you even start. If you just read fantasy, then you’re going to know all about the different types of heroes and anti-heroes that inhabit these words, but what about the fascinating characters that inhabit the murky waters of crime noir? What about the everyday Joes and Janes of general fiction?

Real life is the most powerful source of character traits, borrowing from yourself and the people around you, but also make sure to sample from all across the smorgasbord of fiction and non-fiction. See these characters in action. Take note of how they inhabit the page, and how you might learn from their example. And if you’re writing in a particular genre, like fantasy or crime, read amply from outside that genre. Sometimes your best influences come from less familiar territory.

Character profiles

Not for everyone, but if you haven’t done it before then consider composing a questionnaire for each major character. What they wear. What they’re afraid of. What they carry in their pockets. Even if it seems inconsequential at first, they’re details that might find their way into the story – and more importantly, they tell you about what kind of person they are. The more you know about a character, the more individual presence you can apply to them.

A word of warning here: over-planning and getting lost in adding more and more detail to profiles rather than actually writing the story is a potential hurdle. Just like with planning a plot, know that there’s a time to step away from the planning and actually do the writing.

Dialogue

Always re-read dialogue out loud. Get a sense of the voices of your respective characters and what language they might use. Not every character is going to use the same language, or even have the same vocabulary. Accents and clipped tones (e.g. saying ‘ere instead of here) can be useful, but also easily overdone. Break down any long passages that wind into exposition and backstory, and keep conversations quick and flowing, punctuated with physical cues – your characters are more than talking heads, after all. Everyday speech is always complimented with hand gestures, facial expressions and so on.

Lengthy conversations or group scenes with extensive character interactions can be tricky – it’s a lot to juggle at once to keep characters active, authentic and grounded in the world around them. But it will get easier with experience.

Affect them

After a character is developed enough to be able to step into any scene intact and three-dimensional, the real fun begins. Because for all the grounding a character might have, and however much personality they might have, they can’t be an entity among themselves. They’ve been built up as works of art, but it’s time for them to learn that they’re not untouchable.

Affect your characters. Allow them to react to the world around them. Hurt them, badly if necessary. Force them into a corner where they might reconsider themselves, and their own fundamental traits that you worked so hard on refining – unless they’re the sort of person who ignores all opportunities for self-awareness, in which case see it through to the bitter end. No one is permanently static, so your characters should share the same state of flux as real people.

What do you do?

Everyone’s got their own tricks to refining their own characters. What are yours? Where do your characters come from and how to you develop them from their beginning caricatures into the bundle of traits and quirks that inhabit your work?

Beau Hillier | Editor, page seventeen

On a Winter’s Night

March 19, 2015 A little while ago, I was asked about the ways I gather material to write, and I thought of the sound walk I joined during the midwinter jazz festival last year. It was, I think, a good way for a writer to enter into a scene, to become immersed in it, a way to see beyond the preconceptions and assumptions that often blind us to the nuance of everyday life.

A little while ago, I was asked about the ways I gather material to write, and I thought of the sound walk I joined during the midwinter jazz festival last year. It was, I think, a good way for a writer to enter into a scene, to become immersed in it, a way to see beyond the preconceptions and assumptions that often blind us to the nuance of everyday life.

We set out in the early evening, a small band of strangers weaving our way in complete silence through the Saturday night crowds in Melbourne. Leaving Federation Square, we trailed past the drifts of conversation and gusts of laughter floating above the crackling waters of the Yarra River, through the diners chattering over coffee and wine in Degraves Street, to the jostling shoppers and revellers in the Bourke Street Mall. From there we wound our way through hallucinatory laneways lined with silent wolves, monsters with louring green eyes and a large, reclining cat in fishnet stockings, before returning to the forecourt of Federation Square.

Interestingly, one of the first places we visited was a multi-storey car park. Normally I would notice very little in such an unlovely place. Perhaps I might be conscious of cars sneaking up behind me, but I would be in a hurry to leave that temple of fumes. This time I was impressed at a visceral level as I stood looking around a vast, monolithic echo chamber. I was conscious of the titanic forces buttressing the construction, and in awe of the tons of concrete raised above my head. I could almost feel the sound, bouncing and echoing, reverberating off the hard surfaces. Underlying this, there was a subterranean buzz, a frisson, as people arrived in their evening finery, the men in sharp suits and women, with hair swept high, draped in shimmery confections falling to the oily, polished floor.

At the end of our walk, we were free to speak but I was reluctant to break the spell, even though I had gathered a swag of sights, sounds, smells, ideas and impressions and couldn’t wait to share them. Without the threads of chatter to connect me I felt very separate and alone in my skin, but, at the same time, awash with sensation, tingling from the chill of the night air and intoxicated by the parallel world I had just entered.

The experience was intense but so easy for anyone to conjure up. In many ways it was the exact opposite of a hot shower. Alone in my cubicle, I close my eyes, toss my head back and wander for a few moments in the outer reaches of my mind. My focus is entirely inward as I relish the play of hot water over my skin. In contrast, listening on a sound walk is focused entirely on the outer world. It is a journey so strange, so other, that it is like stepping into a foreign city. While I was not consciously trying to be mindful because I was listening with a little more care, all my senses seemed to chime in.

Lisa Roberts

– Assistant Editor.

Writing Well Pays Off

March 12, 2015

In life, we’re always accumulating knowledge. We accumulate it through what we read, what we watch, the people we interact with, our experiences, our successes, and our failures. We are, for the most part, knowledge-gaining machines when you consider that we start off our lives only really knowing that we should cry when we’re uncomfortable or insecure.

We also gain knowledge from some of the unlikeliest sources. Did you know it takes the average human seven minutes to fall asleep? I read that in a Stephen King novel decades ago – I don’t recall the novel, but I’ve always remembered that fact. We are surrounded by information. It comes in various forms and titbits, regardless of the vehicle.

Some of it becomes essential to us personally or professionally. All the knowledge I’d gain at home in working with computers, software like Word, and online platforms such as WordPress, I was able to take into work. When I was developing this knowledge base, I didn’t realise how useful it would become to me in a professional environment. I thought I was just screwing around.

Sometimes, information seems either surplus to our needs, or just plain old unnecessary. When we die, how much stuff will we know which we never used, was never useful, and/or had no real merit in our lives? Learning it took seven minutes for the average human to fall asleep was – if nothing else – an interesting titbit.

Many would argue that contemporary schooling is replete with lessons that are not germane to real life. Back in Year 9, one history teacher (who eventually became principal of our school) insisted we memorise every state in the USA. As a 14-year-old living in Melbourne, Australia, I didn’t understand the relevance. Similarly with classes such as Legal Studies and Accounting. If I’m ever up on a murder charge, it’s not like I’ll defend myself because I took Year 9 Legal Studies.

Of course, some of these classes exist only to broaden our minds in directions they may not have gone otherwise. Additionally, they’re there to act as tasters. For some, they might be the platform to pursuing careers in these fields – for some. There’s a key phrase, though. It gets you thinking: what do we learn in life that would seem essential for all?

The answer is simple: writing.

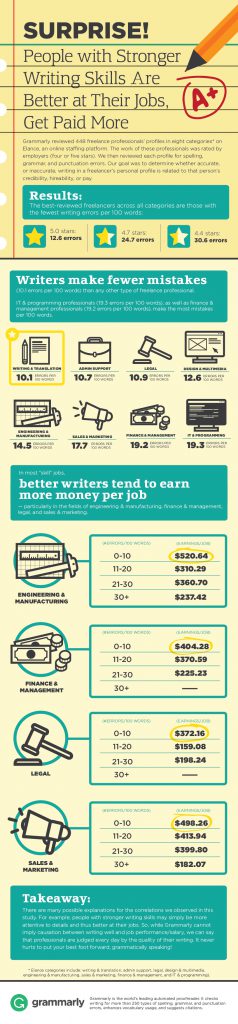

The good people at Grammarly have allowed us to repost the image you see running alongside this blog, which studies how people with stronger writing skills are ‘are better at their jobs, [and] get paid more’. Take a look at the image (you can expand it by clicking on it) and note the differential in errors between professions, as well as salaries.

Grammarly concludes:

There are many possible explanations for the correlations we observed in this study. For example, people with stronger writing skills may simply be more attentive to details and thus better at their jobs. So, while Grammarly cannot imply causation between writing well and job/performance salary, we can say that professionals are judged every day by the quality of their writing. It never hurts to put your best foot forward, grammatically speaking!

Writing well requires something else, though: innovation.

Writers operate in a constant state of innovation. We consider the perfect word, pursue the perfect phrasing, write and rewrite ourselves in our heads before we even get a letter down on the page, and then we revise ourselves on the page. Writing well is, in fact, both a state of high achievement, and improving on everything we’ve done before.

So are the benefits any surprise?

Thanks again to Nikolas Baron and Grammarly.

LZ.

Everyone’s a Critic

February 26, 2015 The rise of the blogosphere (is that the official term now?) has enabled countless individuals to establish an online presence and a platform for public discourse. There’s a blog for everything and everyone, with numerous writers of all stages of development contributing to a vast and evolving network of content.

The rise of the blogosphere (is that the official term now?) has enabled countless individuals to establish an online presence and a platform for public discourse. There’s a blog for everything and everyone, with numerous writers of all stages of development contributing to a vast and evolving network of content.

This is great. It allows everyone to be heard and to find an audience. But it hardly needs to be said that the internet is a pretty negative and hostile place a lot of the time. The phrase ‘don’t feed the trolls’ is now a common warning – born from the fact that hordes of users just want to watch people get irrationally angry. We love seeing anger and outrage. We love being angry and outraged. It’s cathartic if nothing else.

Most writers know the impact of criticism. Especially anyone involved in workshops. We weigh our words so that we provide constructive feedback while pointing out the flaws in someone else’s writing. Most writers know how devastating a badly-worded comment can be to the recipient.

But outside of the workshop environment, the claws come out. A writer who can practice this diplomacy can still be guilty of the same pointless savagery in a public field.

I don’t want or need to point fingers or provide links. Just think about the reactions to modern fads in publishing and other creative disciplines. Fifty Shades of Grey. Twilight. The Da Vinci Code (yeah, remember that one?). The public discourse goes beyond satire or actual criticism and turns into a feeding frenzy over a popular piece of work that’s perceived to be irredeemably flawed. We take joy in it. The brutality becomes a fashionable statement. The work itself can lose its own identity. The work’s flaws become the identity.

That isn’t to say that the criticism is invalid. Everything cited above carries its own issues and shortcomings. As does all writing, in varying degrees.

Anyone who’s seen the animated film Ratatouille knows the critic’s monologue. It’s pretty apt for such a brief discourse on the status of a critic – both professional and amateur – and pointing out the responsibility held by anyone who seeks to appraise the work of another. A responsibility that has evaporated with the expansion of the blogosphere.

In the meantime, let me just wind back the heavy-handed social commentary so I can actually get to the point of all this lip-flapping. I wanted to bring this up because the way we perceive and apply ourselves to the creative work of others is important. Especially as creators ourselves.

A good writer is capable of seeing the virtues and shortcomings of someone else’s work in equal measure. In my opinion, part of the evolution in becoming a good writer involves knowing how to approach everything you consume as a blank slate – something to learn from. It might be how to pull off something remarkable, or how developmental or thematic flaws may manifest in an otherwise perfectly marketable and successful work of writing.

I think most writers know this. But the constant vigilance in applying this principle is important. Yes, Fifty Shades of Grey, to take one example, is widely acknowledged as being consistently flawed in its narrative. You might even say it’s a bad book. (Note that I have neither read Fifty Shades of Grey nor seen the film.) But as a produced work that has found a worldwide market, it still has more value than most of the mud being slung its way. I don’t defend its content, but I do defend its existence.

By all means, be passionate in your convictions about whether something works or not. But know what you’re doing when you vocalise those convictions, and how you do so, specially if you’re placing it in the shark-filled waters of the internet. Know the responsibility you carry when you become a commenter on the efforts of others. Not just to protect their egos. But also for self-development as a writer – as someone actively participating in the exact same network that hosts all these pariahs of publishing.

It’s one thing to condemn a book like Fifty Shades of Grey for being popular when it supposedly doesn’t deserve it. It’s a bigger thing, for your own craft, to consider why it’s popular and what can be learned from it – and how the approach can be refined to avoid the same pitfalls. That’s part of what it means to develop as an active writer.

Beau Hillier | Editor, page seventeen

The Fellowship of the Wing

February 12, 2015 At 7.00 pm, on Wednesday night 18th of February, Busybird’s Open Mic Night returns for 2015.

At 7.00 pm, on Wednesday night 18th of February, Busybird’s Open Mic Night returns for 2015.

Regular readers of this blog or our newsletter will know our spiel: Open Mic Night is a great way to see how your material connects with a live audience, to meet and chat with like-minded people, and simply to promote yourself and your work. It’s also a great developmental tool – as a writer, you will be required to read publically at some point in your career. You might get a book deal, and need to read at the launch. Or to give a reading at a bookstore or library. Public reading is the little brother to writing.

And all that’s true.

What’s more, very simply, Open Mic Night is fun. Take all the facets of professional development out of it, and Open Mic Night is an entertaining night out, offering something for everybody, whether it’s a poem to be moved by, or a story to laugh at. Diversity is one of Open Mic Night’s strongest features.

Perhaps most importantly, since Busybird has been running our Open Mic Night – since midway through 2013 – we’ve developed a sense of community. There are regulars who attend unfailingly, revelling in the delight of sharing their work with others and chatting, whilst new attendees are always surprised about the welcoming, supportive, and nurturing environment.

This year, we’re taking the nurturing one step further.

This year, Open Mic Night is going to be a little bit different.

Previously, there’d been three staples of Open Mic Night.

Firstly, you haven’t been required to book. That remains exactly the same. You don’t have to book. Just show up. It’s that easy. Most people actually like to show up a bit earlier, and chat with others. If you want to read or sing or perform, you just have to put your name down on the running sheet for the night – a warning: putting your name down last on the running sheet does not mean you will be called up last. The order is actually randomised by our emcee for the night, Blaise.

Secondly, we provide refreshments – there’s always something to drink, and nibblies. This is also staying the same. There’ll always be something to satiate your thirst, or satisfy your hunger.

Thirdly and finally, to attend Open Mic Night we’ve requested a gold coin donation. This is where we’re going to do things a little bit differently. Now, we’ll be charging a $5.00 entry fee. Part of this will cover operational expenses for the night (providing the drinks and nibblies, etc.).

But part of it will be pooled in a fund for the Busybird Creative Fellowship.

The Fellowship is intended to help a fledgling artist – a writer who’s had less than three publications, or an artist wishing to exhibit for the first time – improve on their craft through mentoring, use of Busybird facilities, free entry to our in-house workshops, discounted publishing services, and a cash prize of $500.

This is our means of trying to give back to the writing community, and to help somebody develop their craft through our experiences and skills and resources.

Applications for the Busybird Creative Fellowship will open Thursday 1 October and close Friday 30 October 2015. The Busybird Creative Fellowship has a page on our website here and a Facebook page here. We also have a Facebook event for Open Mic Night here.

At $5.00 for entry night, Busybird’s Open Mic Night still provides an entertaining and cheap night, so we hope to see you all there!

LZ.