Blog

Welcome to the Busybird blog, where you can find helpful articles, updates, industry news and more. Make sure you stay up to date by signing up to our newsletter below.

Writing Your Story

November 27, 2014 A lot of people want to write their life story.

A lot of people want to write their life story.

And yet a lot of people have the same query: Who’d be interested in reading about me?

The answer? Sombody. That simple.

Wherever you are in your life, you’ve gone through experiences that are, in all likelihood, both relatable and useful to others.

Here’s a basic example: you’re a survivor of an illness – it might be cancer, it could be depression, it could be anything. You were low, and didn’t think you’d make it. But you went through the hospital system, tried some alternate treatments, had some ups and even more downs, but you pulled through.

Would you think you’re the only one who’s gone through this sort of experience? The knowledge that you haven’t, might seem to make it common, thus is there any point writing about it? But think about your ups, your downs – there’s a very good chance that somebody out there had even more downs. They might feel even more hopeless. Yours might be the story that helps them through whatever they’re going through, physically, intellectually, spiritually, and/or emotionally.

You have something to offer.

Or maybe you don’t believe that’s the case. Perhaps you don’t believe you’ve had anything significant happen to you. You might just be a divorcee with two kids who had to re-join the workforce following your separation so you could support your kids and your household. How many people would this scenario apply to? Thousands? Tens of thousands? If you were able to make a success of your life following a divorce, yours could be the story which inspires others in a similar situation to do the same.

Or maybe you believe you’ve had even less than that happen to you. Possibly you’re in a happy marriage – forty years in the same marriage, working the same job, living in the same house. Nothing to talk about at all. Other than forty years in the same marriage, working the same job, living in the same house. That in itself is an accomplishment. Not a lot of people can boast the same. How do you do it? What do you have to offer others who may be pursuing a similar sort of solidarity?

The point is we all have something to offer. We mightn’t believe it, but if you think about your life, we all have a message to convey – a message that an audience out there might be waiting for.

Think of it this way: if you were a reader, and were looking for a memoir, biography, or autobiography written by an everyman that could help with some aspect of your life, what would it be? Is it something grandiose? Or something simple? Is there something you believe you have to share?

If you have a story, a message, you want to shout to the world, then it is up to you to write it. Granted, it mightn’t lead to fame or fortune – so few books do. And a commercial publisher mightn’t pick it up simply because it is by an everyman – there are more than a few examples where a commercial publishers has descried a story told by an everyman, but picked up something similar by a celebrity, because the celebrity’s name would publicise and sell the book for them. So if you’re going to write, you need to be clear about why you’re doing it. You also need to be clear that you may need to self-publish (either in print, or digitally) to get your story out there.

Here’s some tips, if you consider taking up the challenge:

- Be yourself: don’t try and sound like somebody you’re not. If you have a story to tell, it should be told as only you can tell it.

- Be honest: just tell the truth. Don’t embellish. Don’t twist. It will always catch you out in the end.

- Be searching: a lot of people who write autobiographically only skim the surface of their lives, especially in early drafts. It might hurt to go deep, to expose yourself and leave yourself vulnerable, but readers respond to vulnerability and raw truth.

- Observe a chronology: it’s a simple structure. Don’t jump forward. Don’t go back. Just stick to what happened, as it happened.

- Avoid waffling: don’t believe that more is better. It’s not.

- Avoid repetition: trust that your reader is intelligent enough to get the point the first time. They only need it once. Repeating a point or, worse, belabouring a point, only dilutes it, (unless it’s done stylistically for effect).

- Don’t write to a word count: your story is as long a it needs to be, no more, no less.

- Be fearless: if this is an endeavour you’re going to pursue, then leave nothing behind. Spend it all on the page.

If this is the sort of writing that you’ve considered pursuing, or want to pursue, but always disputed whether anybody wanted to hear your story, think about what you’ve learned and, remember, we all have a story to share.

LZ.

There and Back for CMT

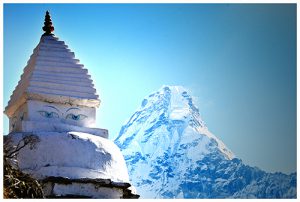

November 20, 2014In March-April of this year, Busybird’s own Kev Howlett trekked up to Mount Everest Base Camp and back, taking photos for a gorgeous full-colour coffee-table book, Walk With Me, as well as an exhibition of the same name, to raise funds for CMTA Australia.

Here’s an interview with Kev, as we prepare for the launch this Saturday …

Tell us a bit about your background

Tell us a bit about your background

I was always good at art at school and after deciding not to join the Air Force I ended up at Preston College studying Finished Art. After a year, my art teacher said I had a flair for photography and might want to think about changing courses. After a bit of back and forth I decided to swap to photography and I completed the two-year course.

I got a work experience placement at a commercial photo studio at the end of my final year and they liked me so much they offered me a job once I left school. I worked there for a few years as an assistant and when the senior photographer – my mentor – decided to leave and go freelance, he asked me to go with him. We worked together for many years until I started getting my own work and then freelancing myself.

I worked in lots of different studios photographing everything from cars, food, fashion and products through advertising agencies. I then worked for an electrical company full-time running their in-house photographic studio, which was great to grow from a primitive analogue studio using old cameras and film to a fully modern digital studio. I ended up setting up one of the first high-end digital studios in Melbourne at the time. I had Kodak and Nikon reps visiting me regularly to calibrate their new cameras and software as we were all in a development stage of the digital revolution.

Seven and a half years there I then started doing technical illustration for Ford’s Global Catalogue on the side from home after the day’s other work. Blaise and I did this together, and part-time jobs on the side; this is where Busybird grew from.

After many years of that and being so busy we couldn’t handle any more, Ford decided to give all our work to India and South America where monkeys were doing it for peanuts. So there we were with no clients and all this equipment.

Luckily, Blaise and I saw it coming for a while so we had the publishing side slowly forming and as we lost Ford we concentrated on clients who needed books made. I did it part time for a while as did Blaise, although she was working full-time at the library and doing Busybird at night.

About eighteen months ago we spotted this building for lease while out walking our dog one night and rang the real estate company to have a look inside. It was six months earlier than we had thought about moving the business out of home but we took a risk and here we are today, both employed full-time at Busybird with a busy and bright future and a publishing house. It has been a long journey but now we look back it’s kind of what we were always aiming for and where we always saw Busybird going.

And how about CMT …?

And how about CMT …?

CMT (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease) is a nerve degenerative disease that our oldest son Dylan has. We had never heard of it until Dylan was diagnosed with it so it has been a learning curve for us as to what it is and the effects it will have on him. We first noticed it when Dylan was in his early teens. He played football for a local club and up to this stage was excelling. He loved it with a passion and I think he thought it might be a career one day.

After noticing he was slowly starting to lose his impact on games, lag behind the others, and fall over a lot more than usual we got him looked at and the normal GP didn’t really have any clues as to the problem. After seeing a podiatrist he first mentioned we should get him checked for CMT so we did. It turns out he has it but as research is very limited, they are not quite sure the type he has because there are new strains being discovered all the time. All we know is that he doesn’t have the most common type, which is very quick-developing and debilitating.

The effects Dylan suffers from are his feet are curling up (hence the falling over) and he was losing sensitivity in his feet and hands. As there is no cure or treatment the only option for him was to have both feet totally reconstructed. This was all as he started his last year of high school VCE so he had to cope with a lot during that year. They operated on one foot with sixteen weeks recovery and then the second so his whole year going to school was interrupted and he was in a wheelchair or on crutches for most of it. He passed his year after missing large chunks, so a great effort on his part.

The reason for my fundraising for CMT was the fact I wanted to spread the word on this and inform others as to its existence. I have loved talking about it and watching people learn and know more about it and what Dylan has had to go through. When I contacted the CMTAA (Charcot Marie Tooth Association Australia) and said I wanted to raise some money for them I remember their humbleness and gratitude toward my offer.

I made a statement that I would love to see a cure or at least some helpful medication developed for Dylan in my lifetime, so hopefully my little trek and efforts are helping that become reality.

What made you want to climb to Mount Everest Base Camp?

What made you want to climb to Mount Everest Base Camp?

I had heard about Base Camp in the past but hadn’t really looked into it much until a friend of mine approached me and said we should try it. Both of us have kept reasonably fit and thought that as we were approached the big five-oh we should do something a little adventurous. Both of us are photographers and we knew of some other photographers who had done it. We thought it would be a great place to do something hard on our bodies but also an amazing place to photograph.

After doing some research we both decided it was the adventure we were looking for so set about planning it. After meeting more and more people who had done it or knew people who had, we heard so many horror stories of attempts gone wrong and abandoned that secretly I was a little worried if I could get there. There were times on the trek I thought, What the hell are we doing? but we got there and back and lived to tell the tale.

And how did the idea for the book, Walk With Me, come about?

And how did the idea for the book, Walk With Me, come about?

Well, being a photographer I always thought I should do something with my photos rather than store them on my computer and forget them. I think it was after that, that we came up with the idea that we could have a reward for pledges to help make the book a reality, and that we could use the book as a way to raise money for CMT.

The Walk With Me title came to us and felt perfect. I wanted the people who took part in my fundraiser to, in a way, come with me on the trek, walk it and feel a part of the experience.

I tried to capture the Walk With Me theme in my photos so when you look at the photos it’s like you are looking out at what I was seeing and feeling. I also thought since people with CMT like Dylan probably will never be able to try such a long and strenuous trek with their condition, I would bring it to them in the book. I love the title as it sums up so much of what the whole project was about.

What was it like taking photographs of the trek?

What was it like taking photographs of the trek?

My photographer mate Norman – who I went with – and I agree it was not the photographic trip we had assumed it would be before we left. We thought we would have time to play, set things up and wait for conditions and light to be perfect.

Well, that wasn’t the case at all.

The trek is very demanding physically and with time so we were always on the go. The sherpas would say zoom, zoom after five-minute rests and off we went again. Nearly all the photos we got were on the move, shot as we quickly saw things, which made it a little tough. With limited camera battery charging opportunities we were always worried about draining all of our batteries and losing use of our cameras so we couldn’t even preview our photos to see if we had gotten what we wanted. We were in a sense shooting blind, just relying on our skills and knowledge to correctly expose and frame the scenes.

Most trekking days were planned to start early in the morning and get to camps early afternoon, so Norm and I thought we would then have the afternoons to go off and set up shots and capture sunsets, etc. Well, as it happens, in Nepal the mornings are crisp and clear but by 1.00 pm the clouds form over the mountains and come in to white the whole place out. So there went our plans.

Another thing I tell people is that there really wasn’t a lot to photograph. Now that may sound weird as we are walking through the Himalayas, one of the most stunning places on the planet. The reason I say this is that the place is amazing, the mountain scenes and hilltop villages were stunning but after a week of photographing them we were looking for something else, something different.

Most villages were the same and as we turned around every corner another amazing mountain scene showed itself and, like anything, you get a little blasé after a while. I wanted to photograph the local people and capture their life and culture, but again I was blocked a little. The trail we were on is quite full of tourists all year and the locals I guess are a little over having cameras pointed at them. Most times you try to photograph them they yell at you or ask for money, children would yell no at you and run away. Although I got some lovely people photos overall it was like pulling teeth and not as easy as expected.

I think I took the right camera and gear and had a good system worked out where my camera was in my hand all the time because things happened fast so you had to be ready. Walking over steep rocky ground meant most of the time you were focused on the feet of the person in front of you so you picked your walking line and didn’t slip. It was a real effort to look up, see what was around you and appreciate it. It was quite annoying to just see the backs of people in front of you all day but that is the nature of trekking. Stopping, even looking back to where you had just come from now and then, was the way to capture the scenes from different angles.

What personal and professional achievements did you get from the climb?

What personal and professional achievements did you get from the climb?

I am a very competitive person so the idea of failing to get to EBC was a scary thought. I had 80 people pledge money and who were riding the trek with me so to come home and say I didn’t quite get there wasn’t an option. I did lose my appetite for a week or so on the way up and I must admit I was running on empty most days. I couldn’t even get plain rice and bread down. Our main sherpa, Roy, was quite concerned with me as he saw me refuse most meals. He wondered how I was still going with the little I had eaten but I did and surprised him and myself.

On a professional level I guess I learnt I have the skills and experience in photography to handle tough conditions and time limits. We were shooting blind and quick and I was adjusting the camera manually in most cases to compensate for light and snow etc. So when I finally got to sit down and check what I had captured, I was pleasantly surprised my instincts had been correct in most cases.

Are you happy with the final product?

Are you happy with the final product?

Yes I am. It has been a long process sorting through over 3000 photos and trimming them down to my best 300 or so. Then sorting into an order and theme. It took quite a few hours of putting all this together and I do love the photos I have used and how they are presented. I am not a very ‘look at me’ kind of guy so I must say I am a little nervous with the attention the book will get once released. I hope it lives up to and exceeds the expectations of all who are waiting for it.

Any words of wisdom for anybody else with a dream?

Any words of wisdom for anybody else with a dream?

All I can say is that the process from dreaming of something and then doing it isn’t that far apart. It just takes a commitment and a desire to do it. I remember thinking that going to Base Camp was a tale I had heard from others, it’s an adventure others take but not someone like me.

I think back now and smile because all the hard work, sweat and pain to get there has been what the dream is all about. I remember thinking about what people had said before I left: ‘It’s not the destination, it’s the journey’.

That’s how the trek was; eleven days to get to a pile of rocks but that’s just the turnaround point – you still have half of the journey left. I think that’s like a dream. You think of something you desire and as good as it is when you finally get it, you find it’s the anticipation, planning, waiting, and excitement that is the thrill of the dream.

That’s the journey.

Kev Howlett.

Walk With Me,, the book and the exhibition, launches 3.00pm, 22nd November (this Saturday!), at the Busybird Studio ~ Gallery. If you’d like to come, please RVSP us by calling or emailing, or by saying yes on our Facebook event.

All the pictures here were taken from the outtakes page of Walk With Me.

P17 Issue 11 Reflections – Joshua Coldwell and Anne Hotta

November 18, 2014 One more day. That’s it. That’s as long as we need to wait for the new issue to be available.

One more day. That’s it. That’s as long as we need to wait for the new issue to be available.

From 7pm on 19 November, Issue 11 is live and ready to go. I hope you’re all as excited as I am – please come along to the launch and open mic performances at the Busybird studio and help us in celebrate.

In the meantime, a final teaser. Two more contributors have something to share about their work in Issue 11 – hopefully it tides you over for one more day!

* * *

Joshua Coldwell on ‘Swan song’

The inception of ‘Swan song’ came about during a slightly inebriated walk along the beach at St Kilda. A fellow actor I was touring with, Sean Watters, was regaling me of the last moments of one of his friend’s uncles. Despite being quite ill and barely able to speak, the gentleman managed to summon enough energy to land one last line: ‘I wonder how far I’ll kick the bucket.’

So, naturally we got to talking and wondered, what would we say? Sometime after and back in Adelaide, I found myself with a rare treat, two nights off. Two nights with nothing planned. Naturally I went mad within the first hour, but remembered the anecdote of the dying man. Thus after assembling the tale between teaching classes during the day and collating the pieces the next night, what followed was ‘Swan song’.

Effectively, it represents my philosophy on death, one that centres on death’s inevitability. Death is sombre, hilarious, violent, calm, surprising and oncoming, it is what it is, and the best we can do is to not get caught up worrying about it or what we will leave behind. Just have a sense of humour about it, respect it, but don’t dwell on it, otherwise it’ll be there before you know it. Death can be awkward like that.

Joshua Coldwell spends his time treading the boards of Adelaide’s theatre scene in various on and off stage roles. When he is not sinking his figurative teeth into his beloved Shakespeare he earns his keep as a High School biology and chemistry teacher. His students find him ‘complicated’.

* * *

Anne Hotta on ‘The taste of cedars’

The story began with three ideas and gradually unwound.

I was curious about what happens when a person uses religious beliefs from another culture to tackle certain things their own culture doesn’t. Would it be wrongful moral appropriation?

I am also interested in the animistic spirituality of Japan – where I lived for a long time – and how it infuses quotidian activities. That Natural beauty and mystery can permeate as deeply as it does, is fascinating for a foreigner.

My third preoccupation was with inter-cultural relationships and how ‘east’ does actually meet ‘west’. Love interests us all and writers try to capture its essence, whenever and wherever.

Perhaps three concerns are too many for the slight frame of the short story, but this genre also allows for inference, imagery and the unspoken. I felt I could indulge my preoccupations to some degree without any disloyalty to the form.

When I first went to Japan, the sensuous aspects of climbing up to a Shrine, the trees, smells, sounds and then the place of worship, made a deep impression. The Jizō shrine dedicated to babies who have been aborted affected me greatly, especially the belief that these beings had not yet atoned for the sins they carried at birth. I imagined the grief it would bring to the ‘mother’; it reminded me of anecdotes I have heard from friends about what abortion can do. It seemed possible that a western woman, might reach across the divide to find comfort.

Anne Hotta has written non-fiction articles for newspapers, journals and magazines, but would like to be a successful writer of fiction. She has had a story published by Overland and received an Honourable Mention in the Boroondara Literary Awards.

Workshop

Wikipedia: Beginning with the Industrial Revolution era, a workshop may be a room or building which provides both the area and tools that may be required for the manufacture or repair of manufactured goods. Workshops were the only places of production until the advent of industrialisation and the development of larger factories. →

Wikipedia: Beginning with the Industrial Revolution era, a workshop may be a room or building which provides both the area and tools that may be required for the manufacture or repair of manufactured goods. Workshops were the only places of production until the advent of industrialisation and the development of larger factories. →

Wanted: Verb

November 13, 2014 If you wanted to hang a picture, and had to hammer a nail into the wall, you’d use a hammer for the job. Sure, you could probably use the blunt end of an axe, or a heavy-heeled shoe, but the best tool for the job would be the hammer, because that’s what hammers do.

If you wanted to hang a picture, and had to hammer a nail into the wall, you’d use a hammer for the job. Sure, you could probably use the blunt end of an axe, or a heavy-heeled shoe, but the best tool for the job would be the hammer, because that’s what hammers do.

They hammer.

When writing, you need to treat your selection of verbs the same way. You need to find the right verb for the right job. It doesn’t have to be a fancy verb, it doesn’t have to be a verb that’ll send readers to the dictionary, it just has to the verb designed for that particular job.

Of course, there are lots of different verbs that do similar things. If this occurs, then you need to find the verb most appropriate for what’s happening. Sometimes, this is easy. Sometimes it’s not.

Consider this scenario: Bob’s partner Gloria sits on the couch in the lounge. The kitchen explodes. Bob wants to get Gloria out of there fast. So how does he grab her from the couch?

- Bob grabbed Gloria’s wrist and pulled her from the couch.

It’s simple. No extravagance here. And it works … doesn’t it?

Yes, it works, but lacks the immediacy the situation demands. The damn kitchen’s just blown up! And he’s just pulled her up, like he’s inviting her to dance? Uh uh. So what’s the alternative?

- Bob grabbed Gloria’s wrist and pulled her quickly from the couch.

That tells us more, right? He hasn’t just pulled Gloria up; he’s pulled her up quickly! But the reality is if you need an adverb (quickly) to modify your verb (pulled), then your verb’s probably not the right tool for the job. You need to find a verb that is going to do the work of, in this case, ‘pulled quickly’.

- Bob grabbed Gloria’s wrist and yanked her from the couch.

How’s that? Better? At the very least, ‘yanked’ communicates the immediacy and urgency the situation demands.

As writers, we develop our craft through one primary tool. Can you guess what it is?

If you said ‘vocabulary’, well, you’re not quite right. A good vocabulary is important, but the primary tool is actually ‘habit’. We like to say things a certain way, use certain phrases, develop certain idiosyncrasies – this becomes our voice. That’s fine, but if we develop the habit that we just go with the first thing that comes to mind, then we won’t think about the verbs (or words) we use.

Stop. Think about it. Look at your narrative. Are the right words doing the right jobs? Or do you have half-assed workers just making a good fist of it? Or, even worse, do you have imposters?

- Gloria shouted at Bob, which caused Bob to be upset.

Or:

- The wind blew across the river, causing the surface to ripple.

At least in the case of yanking Gloria from the couch, pulling is in the realms of the same action – pulled, yanked, jerked, etc. Caused? Well, it tells us something happened, it just doesn’t tell us how. It’s a trigger that turns the actual verbs (upset and ripple) into adjectives. This dilutes what’s going on. Here, we should put the verbs back in charge.

- Gloria shouted at Bob, which upset Bob.

And

- The wind blew across the river, rippling the river’s surface.

Or, with this second example, even something like …

- The wind rippled the river’s surface.

As an aside, note with the second example of the river, we leave out ‘The wind blew across the river’, because that’s now become implied. If the wind rippled the river’s surface, the wind must be blowing across the river.

In any case, aren’t these examples better than the ones using caused?

Get in the habit of thinking about your writing, about the words you’re using, and finding the right ones for the right jobs.

LZ.

P17 Issue 11 Reflections – Kevin Gillam, Holly Zwalf and Ben Grech

November 11, 2014 In just over a week, the wait is finally over. The open mic night on 19 November is open invitation, so come along if you can and celebrate the launch of Issue 11 with us!

In just over a week, the wait is finally over. The open mic night on 19 November is open invitation, so come along if you can and celebrate the launch of Issue 11 with us!

If you’re curious about some of what you can expect in the latest offering from page seventeen, read on: three more of our latest contributors have a little something to share about their work. Some of it will resonate now, some will hit you later after you’ve read the issue. Either way, maybe there’s something in their path of inspiration that you can relate to, or tale something from? Hmm…

* * *

Kevin Gillam on ‘The hush’

‘The hush’ was written as an attempt to create a poem with an utterly tangible syntax, using some of my favourite and deliberately obscure topics as content. The essence of the poem is in the creation of its argumentative voice, one that spins a kind of distorted logic in the hope of being convincing. My own writing style is very like this – always collecting phrases, thoughts and snatches of conversations, particularly from philosophers and scientists in discussion.

Kevin Gillam is a West Australian writer with three books of poetry published: other gravities (2003) and permitted to fall (2007) both with Sunline Press, and ‘songs sul G’ in Two Poets with Fremantle Press (2011). He works as Director of Music at Christ Church Grammar School in Perth.

* * *

Holly Zwalf on ‘Out of season’

One cannot help but be aware of an absence that clings to Australian landscape poetry; an absence that seems to suck dry our already barren continent, leaving it flat and drained of colour. The omission of the human inhabitants of these landscapes is sometimes conventional and often political, performing a poetic terra nullius through verse.

I am deeply in love with Australia’s landscapes but I am soon bored by photographs of mountains or statues or sunsets, unless there is a person located somewhere in the shot. While not explicitly political in its content, through my writing I try to offset the natural environment with the people who inhabit it, to locate bodies and their emotions within a wider ecosystem, and to combine confessional and landscape poetry in an attempt to explore the relationship between the personal and the environmental.

Holly Zwalf is a queer smutty spoken word artist and poet who grew up on a boat, but who gets horrifically seasick. She likes free medicare and hates birds in cages.

* * *

Ben Grech on ‘Pikes Ridge’

I started writing this piece while on exchange in Canada. I loved Montreal, but after a month I was homesick. I began reading Australian literature obsessively. I was ignoring coursework. I demanded my housemates read the books so I’d have people to talk with about them. I took on a heavy Australian tone and lexicon. I caught myself saying things I’d never said before: ‘G’day,’ ‘Ooroo,’ and ‘Beaut’ somehow found their way into my everyday conversation.

As part of my exchange I was accepted into a creative writing course instructed by Kathleen Winter, whose invaluable mentorship has kept me writing. The prose I unloaded onto the class was unquestionably Australian. ‘Pikes Ridge’ began as part of a free writing activity during which I wrote about a young boy admiring a mountain. I knew this was going to be a large part of the narrative. Stories like The Kiss by Peter Goldsworthy and The Boat by Alistair MacLeod, which both revolve around young boys in small towns, immediately became strong influences.

From there the story turned into little unconnected, overwritten vignettes of imagery and narrative. By the end of the course major themes were outlined, tensions were exposed, metaphors discovered, and a narrative structure loosely implemented. That was two years ago. It was ninety percent finished when I left Canada, but the last ten percent has taken hours of editing, rearranging, rereading and thinking about to get it to a place that I was happy to start sharing.

Ben Grech is an aspiring teacher and writer living in Melbourne. Writing has been a hobby since he was young. He started taking it seriously when he was accepted into a competitive writing course in Montreal taught by Kathleen Winter, whose intimate mentorship and advice gives him confidence whenever he writes.