Blog

Welcome to the Busybird blog, where you can find helpful articles, updates, industry news and more. Make sure you stay up to date by signing up to our newsletter below.

Dealing with Rejection.

August 29, 2013 Possibly the most difficult thing any writer has to deal with is rejection.

Possibly the most difficult thing any writer has to deal with is rejection.

It’s something we all face, and it never gets easier. Unless you have the clout of a Stephen King or JK Rowling, you will get rejected. That story you think is brilliant, which you’ve revised so it shines, which everybody tells you is magnificent, is no guarantee of immediately finding a home.

That’s writing – and publishing. It’s a subjective business. Think about a classic: The Great Gatsby is considered one of literature’s greatest novels, but I know people who hate it. Who were bored senseless by it. That doesn’t mean Gatsby is a bad book; nor are those people are wrong. Simply, tastes vary.

Other factors also come into play. Have you correctly targeted your market? You might’ve written a witty satire unfolding as a political drama, yet submit it to a journal who’s interested only in genre fiction. It’s not a great fit, and not one that you should expect to be made.

Or you might’ve written an awesome story about killer robots who take over the world, but have submitted it to a journal who’ve just accepted a story about killer robots who take over the world. If that’s the case, your rejection mightn’t necessarily be based on quality, but on content specifications, i.e. they don’t want two of the same stories.

Similarly, there might be a focus on a certain length. Your 4000-word story on mutant daffodils that rampage and eat a town might be considered fantastic, yet unusable for a journal that has only space remaining for a 2500-word piece. These things do happen.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t make dealing with rejection easier. You can tell yourself the right things – that your piece wasn’t for this particular market, that possibly they didn’t ‘get it’, that they’re all big buttheads – but your ego’s going to take a bruising regardless. That’s human nature.

You could also start questioning yourself. Most journals (and publishers) only provide form rejections, as they simply don’t have the time to personalise responses to everybody submitting to them. (We know, we tried!) So you’ll never know why you were rejected. You’re left with the uncertainty, with the questioning, with an array of possibilities.

And that’s the difficult bit. Writing is very personal. You invest yourself in your work. When your work is rejected, it can be like you yourself are rejected. It’s hard dealing with the uncertainty of why it occurred. The question becomes how you deal with it.

You can take rejection as a sign that your story needs more work. Be candid. Was the story you submitted the best it could be? Were you impatient? Did you just want to get it out there? Or because you were trying to meet a submission deadline? Take another look at it. Or get some feedback from people who can offer you a frank appraisal.

Did you meet their submission guidelines? Yes, sounds stupid. But journals/publishers can get hundreds, if not thousands of submissions monthly. You know one of their quickest, easiest reasons for rejection? Because somebody ignored their submission guidelines. If you’re not going to show them the respect and consideration they expect, then they certainly won’t show it towards you. Make sure you observe guidelines. Don’t assume you’ll awe your market to the extent that they’ll ignore any indiscretions.

Otherwise, if you’re confident your story’s not going to get any better, that it’s formatted correctly, plough onwards. Find another market. Prepare your story (according to their submission guidelines) and send it away. I’ve noticed a lot more markets (particularly US markets) are becoming more and more amenable to multiple submissions, (meaning they don’t mind if you’re sending them a story under consideration elsewhere), so there are always alternatives.

The point is move forward. Rejection hurts, yes. Absorb the blow. Feel sorry for yourself for a time, if that’s going to help you get over it. But do get over it, because it’s all part of the process. And submit again.

You’re a writer, after all. Submitting’s what you need to do.

LZ.

First Drafts: Part 2.

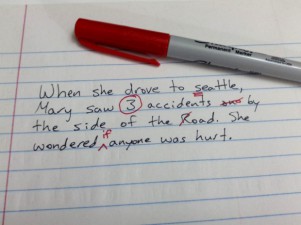

August 23, 2013 Over the next two weeks I’m running the same blog about first drafts. Last week’s blog was my unabridged first draft. This week’s blog is the same blog, but revised. Hopefully, this will demonstrate the necessity for revision.

Over the next two weeks I’m running the same blog about first drafts. Last week’s blog was my unabridged first draft. This week’s blog is the same blog, but revised. Hopefully, this will demonstrate the necessity for revision.

First drafts – how good are they?

Ernest Hemmingway is quoted as saying, ‘The first draft of anything is shit.’ In the August Busybird newsletter, author Ryan O’Neill said, ‘I hate writing first drafts … First drafts are horrible.’

Compared to what the finished product could be, yes, they are. They’re rough, filled with errors, overwritten in some places and underwritten in others. They can be terrible.

But what would you rather have? A blank page or one filled with words? The words mightn’t be the best words, but they give you raw material that can be shaped. Don’t ever besmirch your first draft. Even if it doesn’t work, it shows you which way not to go.

I don’t see anything wrong with my draft, though …

We see so many stories for [untitled] that are great prospects but rough. So often at content meetings we remark how a story is a draft or two away from serious consideration. Some authors (and I know this from my own experiences) are in such a rush to get their story out into the world, they submit it without taking the time to revise, revise, revise. A lot of times, you get only one shot at submitting to a particular market. Make sure you make the best first impression you can.

Go over your work and go over it and go over it until you feel there’s nothing more you can do. Then put it aside for a week or two (at the least). You’d be amazed what you’ll be able to see once you’ve gotten some space from it.

When you truly can’t get anything more out of it, get opinions from friends – and not just friends who’ll give you a perfunctory, ‘Yeah, it was good.’ Develop relationships with other writers whose opinions you respect. Join a workshopping group. Then work on it some more.

That doesn’t sound glamorous at all

No. Many think writing is about writing a story, finding a publisher, and getting a bestseller. Writing is as much about rewriting (multiplied ad nauseam) as it is about writing. It’s hard. It’s frustrating. You’ll grow to dread revision, fearing you’ll miss something vital, or won’t have the capacity (or skills) for improvement.

A lot of great writers are crippled by self-doubt. This is probably the reason: the insecurity of not getting something right or fearing they won’t be able to.

But the hard work is worth it.

When does it end?

This is a question we get during workshops: ‘When do I call it quits?’ There’s no definitive answer. Every draft – as well as every step in revision – is different. Sometimes you may need to go backwards to go forwards, or sideways to find where you are. Some revisions may take a quantum leap in improvement.

As you go, you’ll also learn the difference between meaningful and meaningless revision. Meaningful revision helps you find your way through a draft. Meaningless revision amounts to tweaking, which you could do forever.

Don’t worry. You’ll develop a recognition of what’s substantive and what’s not, when to revise, when to rest, when to seek feedback, when to let go, and when to submit.

Like any muscle, the more you use it, the stronger it gets.

Happy revision.

Oh, before I forget, a postscript …!

Don’t forget Michelle Endersby’s exhibition Floribunda opened Saturday at the Busybird Publishing Studio ~ Gallery. Check out our Events.

One final aside …

This draft is almost two hundred words shorter than the first draft, which is something else to think about.

LZ.

First Dafts: Part 1.

August 15, 2013 This we Over the next two weeks I’m going to run the same blog about first drafts.. The first blog will be my unabridged first draft, replete with typos and whatever errors I’ve made, clunkiness, and whatever issues it may have contain. Next week’s blog will be the same blog, but revised and polished. Hopefully, this will demonstrate the necessity for revision.

This we Over the next two weeks I’m going to run the same blog about first drafts.. The first blog will be my unabridged first draft, replete with typos and whatever errors I’ve made, clunkiness, and whatever issues it may have contain. Next week’s blog will be the same blog, but revised and polished. Hopefully, this will demonstrate the necessity for revision.

First drafts – how good are they?

A few people have commented that Ernest Hemmingway is quoted as saying, ‘The first draft of anything is shit.’ In the August Busybird newsletter, author Ryan O’Neill said, ‘I hate writing first drafts … First drafts are horrible.’ And speaking in terms of the finished product, yes, they are. They’re rough, filled with errors, and usually overwritten in some placed and underwritten in others. Yes, they can be terrible.

However (a good however, too) they give you material to work with. What would you rather have? A blank page staring defiantly at you? Or a page filled with words? They mightn’t be the best words, but they give you raw material that can then be shaped. Don’t ever besmirch your first draft efforts. It’s better than having nothing. And even if it doesn’t work, it shows you which way not to go. Usually, as you write (and as I write), new avenues will occur to me, revealed to me as if the first draft were headlights on a darkened road.

But I can’t make my first draft any better!

Shudder. We see so many stories for [untitled] that are great prospects but rough. So often at content meetings we remark that a story needs a redrafting or two. Some authors (and I know this from experience, from when I was young and an idiot) are in such a rush to get their story out into the world, they submit it without taking the time to revise, revise, revise. A lot of times, you only get one shot at this. Make sure you make the best first impression you can.

I don’t see anything wrong with my draft, though …

Go over it and go over it and go over it until you reach this point. Exact every opportunity you can to improve your draft. Then, when you feel there’s nothing more that you can do, put it aside for a week or two. Get some space from it. Freshen your objectivity. You’d be amazed what you’ll be able to see once you’ve gotten some space from it. It’s like that saying, ‘Can’t see the forest for the trees.’ Well, time to get out of the forest for a little while. Then plunge back into it.

When you truly can’t get anything more out of it, get opinions from friends – and not just friends who’ll give you a perfunctory, ‘Yeah, it was good.’ Develop friendships with other writers whose opinions you respect. Join a workshopping group. Then work on it some more.

That doesn’t sound glamorous at all

No. Many think writing is about writing a story, finding a publisher, and getting a bestseller. Writing is as much about rewriting (multiplied ad nauseam) as it is about writing. It’s hard. It’s frustrating. You’ll grow to dread going back into the forest, fearing you won’t find you’ll miss something vital, or won’t have the words to revise something that can be improved.

A lot of great writers are crippled by self-doubt. This is probably the reason: the insecurity of not getting something right or not being able to. Much better to be oblivious, and just send stuff out into the world once its done, regardless of the quality. But if you’re doing this, you’re not getting the best out of yourself or out of your writing.

When does it end?

This is a question we get during workshops: ‘When do you call it quits?’ There’s no definitive answer. I can’t suggest It’s not like a certain amount of drafts equals magic. But redrafting – if you’ll excuse the cliché – is a muscle. By working it, you’ll learn to judge when to redraft, when to step back, when to ask for feedback, and when to submit.

From my own personal experience, when I was young I’d look at something two or three times and that’d be it. Now, I might look at something ten

You’ll develop a recognition of those boundaries, as well as the awareness of when to push them, when to cross them, and when to let go.

One last note on revision …

It’s also important to recognise when your revision is meaningful and when it amounts to shuffling deck chair. You can juggle words and tweak prose without ever impacting the meaning. Again, this is something you’ll become aware of of your narrative. Try to distinguish when you are shuffling deck chairs and when you’re manning lifeboats. Again, it’s a skill that will develop with time.

Happy writing!

Oh, before I forget, a postscript …!

Don’t forget Michelle Endersby’s exhibition ‘Floribunda opens this Saturday at the Busybird Publishing Studio ~ Gallery. Check out our Events page for more details, or last week’s blog.

LZ.

Floribunda

August 9, 2013 Here at Busybird, we’re not just dedicated to the industry of publishing. We’re also a gallery and open to hosting exhibitions. Already, we’ve had In the Suburbs of the Heart by linvanhek. Our newest exhibition is Floribunda by Michelle Endersby.

Here at Busybird, we’re not just dedicated to the industry of publishing. We’re also a gallery and open to hosting exhibitions. Already, we’ve had In the Suburbs of the Heart by linvanhek. Our newest exhibition is Floribunda by Michelle Endersby.

Growing up in in the natural bushland beauty of the Eltham Shire, Michelle developed an early sense of wonder at the natural world. She saw personality in individual plants and flowers, which sometimes makes her florals and nature studies seem almost like portraits. Her desire was to sweep her audience up in the magic she saw so that they could feel the emotion and intimacy she experienced.

A lifelong interest and involvement with textiles drove Michelle to explore the textural properties of her subjects, be that the velvety petal of a rose or the meandering root systems of ancient Moreton Bay Fig Trees.

A brush with death changed Michelle’s life and strengthened her career as an artist. On awakening from a coma following emergency brain surgery to repair a ruptured blood vessel, she found herself in a beautiful, light-filled rose garden. This vision hastened her recovery and illuminated her path so that she saw the world through different eyes. Surrounded by beauty, Michelle wanted to share her vision with the world.

Floribunda is a collection of twenty of her favourite florals painted over the past four years, a celebration of the many characters that make up the world of flowers and herald the coming of Spring.

Take the time to step back and bask in their colourful splendour.

Floribunda will run at the Busybird Studio ~ Gallery from 17th August to 14th September, and will be launched 21st August, Wednesday night, at 7.30pm at Busybird’s Open Mic Night.

Pitfalls of a Writer.

August 2, 2013 Most writers will have a romantic notion of writing a book, pitching it to a publisher and being wined and dined by the literati as the book skyrockets to the best-selling lists. Sounds good, huh?

Most writers will have a romantic notion of writing a book, pitching it to a publisher and being wined and dined by the literati as the book skyrockets to the best-selling lists. Sounds good, huh?

Since the advent of the internet and digital technology, the traditional paradigm for publishing has changed dramatically. I think it’s fantastic BUT it means that a writer has to think differently too. You might ask why?

The writing game isn’t just about the words anymore. It’s a package deal. It might be better to look at a book as a small business because it isn’t enough to write your bestseller and sit back and wait for the adulation. It can happen but rarely does.

Here are some common mistakes:

- Writing a book for money

- If you think that your book is going to allow you to give up your day job, think again. DO NOT have this as your reason to write a book. If you do all the right things, and your book does well, you may make some money out of it but it isn’t common for someone to be able to retire and write full-time unless you’re someone like Bryce Courtenay. Try to write a book because you feel that you have a story to tell, something to leave behind after you die. It’s a bonus when you make money out of it.

You may be able to make a good living once you have a few books out and have a collective sum of commissions.

- Not having your work edited

- I would love to have a dollar for every time that someone has come up to me and said, ‘I’ve had my book edited, can you help me publish it?’ That editor that they are talking about is often a friend or relative and the book is in no way ready for publication. It doesn’t matter if you plan to submit to a traditional publisher or to self-publish, you must have the manuscript professionally edited. This is just as important for a print book as an ebook.

- Not getting feedback

- If you’ve written a manuscript and self-edited (as so many do), but never shown it to anyone, you are crazy! It’s worthwhile being in a writing group or sharing your work somehow with other writers (not relatives and friends). This should be at different stages of the work: the outline, first draft and final draft. Feedback is crucial to the success of your book.

- Not using Microsoft Word

- There are many programs available to write your bestselling book with but get with the times and use Word. It’s universal, professional and you have fairly good control over the formatting.

- Having only one plan for your book

- Everyone would love to write a book and have it published by Penguin or Allen & Unwin but the changing times have meant that this seems to be harder than ever. This means that in the modern publishing world we need to be more flexible. Plan to write you book and submit it to a publisher. If that doesn’t get anywhere, plan to self-publish. You may find that self-publishing gets you noticed by your dream publisher and you end up being published by them anyway. In the meantime, write the best damned book you can.

- Depending on social media and word of mouth

- You must have a plan for your book once it’s published. It doesn’t matter whether it’s published by Penguin or yourself. Either way it needs to have some marketing behind it in order to get it into people’s hands. The big publishers no longer put lots of money into book tours and marketing, so a lot of it falls to the author to promote themselves.

Writing a book is hard work. Stamina is required. But the people who write and finish a book usually have something to say and feel compelled to share it. Being able to fulfil that need is very satisfying and a good reward in itself, but do yourself a favour and think ahead. The more you put into your book and its life after writing it, the more people will get to read it.

– BvH.